CHINA — When Christine and Steven Coombs bought the Branch Pond Dam more than a decade ago, they intended to restore the historic dam building and restart its water powered grist mill to process local grain again.

They thought the building could become a museum and education center and stand as one of the only examples of a mill of its type in the Northeast.

However, a long-running battle with camp owners and the Maine Department of Environmental Protection over lake water levels, combined with an economic downturn, have put those plans on hold.

Meantime, the large mill building and the dam under it have deteriorated severely and have become an imminent threat to public safety, according to local and state officials.

Sluice gates at the bottom of the dam are broken and malfunctioning, elevating the chance the dam could overtop and damage property and infrastructure downstream, including Route 3, a main thoroughfare. The dam leaks, it has cracks, and it lacks an emergency spillway to reduce the chance of overtopping.

The large wooden building has collapsed partially, and part of the roof is caving in. Town officials worry that if it falls apart, it could crash onto Branch Mills Road, about 25 yards away.

The state wants the dam fixed. The town wants the mill fixed. The Coombses say they want to fix both and restore the historic building.

But after nearly two years of requests from the Maine Emergency Management Agency, nothing has been done.

Now the couple is facing a possible state order that would require them to fix the problems, and town officials are contemplating securing the structure and possibly demolishing it.

The Coombses blame the dam’s deterioration on a water level order the Maine DEP put in place in 2014 at the request of seasonal property owners on Branch Pond.

The DEP order was illegal and unconstitutional, and it disregarded the dam’s structural ability to hold consistently high lake water levels and makes it impossible for them to repair the broken dam, because they cannot open and fix the gates when the water is high, Christine Coombs said in an interview Friday.

“The dam itself is fine,” Coombs said. “We have repairs that we have to do. We have been trying to get them done for many years. We have been stopped by the camp owners from being able to do it.”

But the couples contention — that the DEP order prevents them from fixing the sluice gates — isn’t true, dam safety officials said.

In fact, the water order gives the owners a chance to get written permission from DEP to draw the water levels down below the required limit temporarily to repair and maintain the dam.

The Coombs would not even have to go that far to make emergency repairs, said Mark Hyland, operations and response director at the Maine Emergency Management Agency.

A typical procedure for dam maintenance is to put up a temporary barrier that holds the water level back while work is completed, but there are other options for fixing the structure, he said. In fact, the main problem is that people can’t get under the mill to make repairs because it is too dangerous, he said.

“There are lots of different engineering ways of fixing this,” Hyland said. “They don’t like the order, but that doesn’t have anything to do with fixing the dam.”

‘PUBLIC SAFETY HAZARD’

Christine Coombs said the couple specializes in restoring historic buildings and intends to follow through with their plans to turn the mill into a museum.

They will make the repairs, but they have no timeline because they are affected directly by the weather and have a slim window of opportunity during the summer, when they can work on the dam, she said.

If it wasn’t for their head-butting with the DEP and camp owners on Branch Pond, they would have completed the repairs and restored the building log ago, she added.

“We would love to see it restored,” Coombs said, “but frankly, the camp owners don’t want to see it there. They have been pushing and pushing and pushing and pushing to blockade every step.”

The Branch Pond Dam, also known as the Dinsmore Dam, was built in 1817 and topped with the current mill building in 1914, according to a 2014 dam safety report by state dam inspector Tony Fletcher.

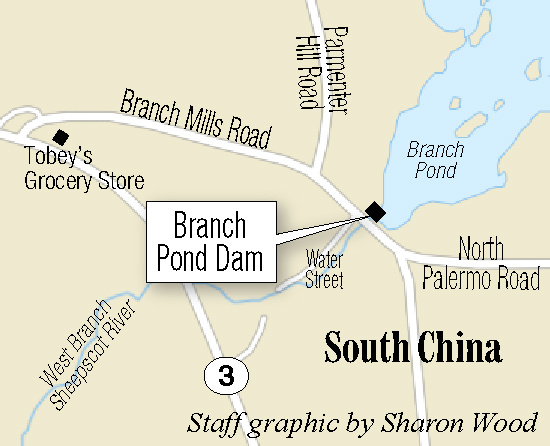

Branch Pond is the headwater of the West Branch of the Sheepscot River.

Until it ceased operation in 1960, the mill was a gristmill, a hydroelectric plant, a shingle mill and a sawmill. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

In the 2014 water level order, the Maine Historic Preservation Commission said a loss of the dam would diminish the historical integrity of the mill, and it recommended the retention of both.

But the structure sustained significant damage several times in the 1990s, and an emergency management report from 2000 listed it as being in “fair to poor” condition.

After the Coombses bought the mill in 2003, they put some repairs into it, upgrading the earthen dikes and installing a storm drainage system. In 2008, the owners installed a cribwork structure to shore up the building, but had to lower the lake level. They lowered it again in 2009 to make repairs to the sluice gates, which were only partially completed, and in 2011 to install a large cribwork under the building, according to the 2014 report.

In his conclusions, Fletcher noted that the dam is classified as a significant potential hazard, which means it could damage private property and public infrastructure if it overtopped or was breached.

Although significant-hazard dams can be well maintained and safe, the Branch Pond Dam was not, Fletcher noted.

In an email to the Coombses after the safety inspection in June 2014, Fletcher said the dam was not operated regularly — the couple lives in New Hampshire and are not usually near the dam — its gates and spillways were inoperable, the mill building was in imminent danger of collapse and the dam was leaking extensively.

“These findings lead me to conclude that Branch Pond Dam is dysfunctional and a public safety hazard,” Fletcher said. “It would be in the public’s interest that the dam gates, spillways and mill buildings be repaired without delay,” he added. The Coombses also needed to update their inadequate emergency action plan in case something did go wrong, and test the plan, Fletcher said.

But over the course of a year and a half, and despite numerous emails between Fletcher, emergency management staff, and the owners, apparently no headway was made in repairing the dam or mill. Instead, the Coombses repeated their argument that the DEP and camp owners on Branch Pond were responsible for the problems.

In an email to Fletcher in July 2014, the couple said they would not repair the dam as long as the water level order remained in place.

“Until the DEP decides to abolish the current water level order on the Dinsmore Dam, we will not invest any more money into the dam and it will continue to deteriorate until it will not hold water at all,” they wrote.

In November, Christine Coombs made the same argument in an emailed response to Fletcher’s continued requests to do something about the dam gates to prevent damage to public roads downstream because of flooding in the spring.

“When the mill finally collapses into the river (which may very well be this winter), we will be pointing the finger of blame at the DEP and the Maine Legislature,” Coombs wrote. “The unchecked power of the DEP (together with the state’s water level law) will destroy another irreplaceable piece of Maine history,” Coombs said. “History that belongs not to them, but to future generations. We will be vocal about their obscene mismanagement which will soon cause yet another burden on the Maine taxpayer.”

DEP spokesman David Madore, in an email Friday, rejected the Coombses’ accusations.

“We disagree with each and every one of those arguments,” Madore said. “The owners had the opportunity to appeal the order when it was first issued and failed to pursue it further,” he wrote.

Under Maine law, the DEP has the authority to administer the water process for nonhydropower dams, and the owners can ask the DEP to reduce the water levels temporarily for maintenance and repairs.

TAKING ACTION

In January, Fletcher filed a recommended dam safety order with the state director of emergency management that would require the owners to make all the repairs and make sure the dam could operate if an emergency developed.

The recommended order had an April 1 deadline, and if the fixes were not made, the state could take all necessary actions to protect life and property, including taking control of the dam or entering the property to carry out the order.

Hyland, the emergency agency’s operations director, said Friday that the order has not been finalized and the agency will meet with the Coombses to go over its concerns before taking action. A dam conference with the couple should be scheduled by early March, he said.

“It will give us time to review our report and be able to talk to us about the fixes we need to do,” Hyland said.

Meanwhile, the town of China also has gotten involved.

In a Jan. 8 letter, Code Enforcement Officer Paul Mitnik informed the couple that the town considered the mill a dangerous structure and a public safety threat and was considering getting a court order to condemn the building and demolish it, or at least to shore it up to forestall a collapse, unless the Coombses provided the town with a repair plan.

In a letter responding to the town, the Coombses said they intended to repair the mill and were proceeding with getting permits from the town and the DEP to install structures for immediate stabilization, but the overall repairs would require a significant amount of time. They then repeated their argument that the DEP order was impeding their ability to make necessary repairs to the dam.

On Friday, Mitnik said he has not heard from the couple and they have yet to apply for a building permit. For the moment, the town is holding off on demolishing the building, he said.

“I didn’t order any demolition. I’d like to see it moving a little quicker,” Mitnik said.

Peter McGuire — 861-9239

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story