HALLOWELL — Federal authorities on Tuesday searched the home of Barbara Cameron, as part of a nationwide manhunt for her ex-husband, James Cameron.

“We’re still working leads,” said Dean Knightly, supervisory deputy U.S. Marshal District of Maine, late Tuesday as at least 10 officers from local and federal agencies searched the house and garage.

Knightly called the search part of a routine investigation. U.S. marshals had left the house about 4 p.m. Tuesday.

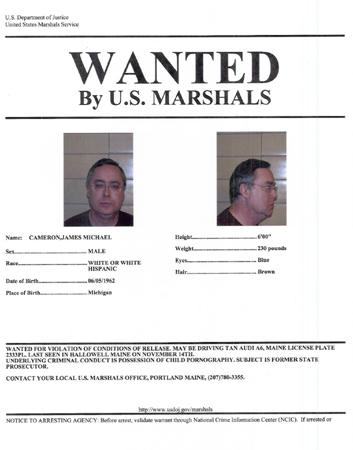

James Cameron, 50, had been free on bail pending a ruling in his appeal of federal child pornography charges. That ruling, which upheld seven of his convictions and vacated six others, was issued a week ago. The state’s former top drug prosecutor was facing 15 years in federal prison — the remainder of a 16-year sentence imposed in March 2011.

After the ruling, Cameron stopped by his ex-wife’s home on Greenville Street and told his son he was going back to jail, according to documents filed in U.S. District Court in Bangor.

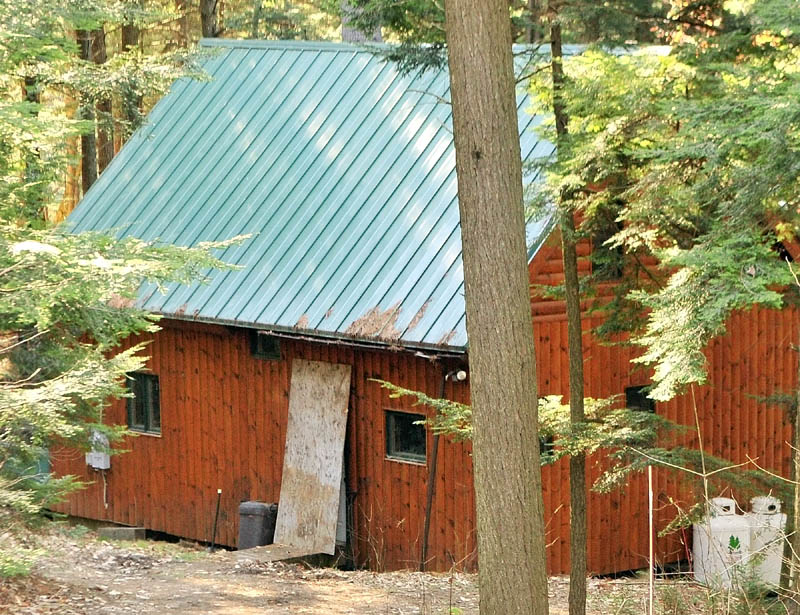

Then he went to his rural home in Rome. By early Thursday he had cut off his electronic monitoring bracelet and fled, taking his car and his laptop, but not his cellphone.

Federal marshals got an alert from the alarm company at 1:47 a.m. Thursday that Cameron left the Rome house without authorization. They tried to call him; he didn’t answer. They tried again between 7 or 8 a.m.

When they went to his home at 10:30 a.m. — a full eight hours after being tipped off that something was amiss — Cameron was long gone.

Authorities said Tuesday they spent the time between when the alarm sounded and the visit to his house determining whether Cameron had violated his bail conditions.

The conclusion that U.S. Probation officials waited to check on Cameron “is not really accurate,” said Donald Clark, assistant U.S. attorney, Tuesday. “From the moment they were aware he was missing, they were attempting to contact him and then locate him.”

The U.S. Marshals Service got a warrant for Cameron’s arrest later Thursday and spent some days searching for him before going public with the manhunt Monday afternoon.

Authorities have said they believed Cameron was driving his car, a tan Audi A6.

On July 2, Cameron crashed his BMW motorcycle in Hallowell. Knightly said Tuesday he didn’t know that Cameron owned a motorcycle but other agents might know where it is. He said the Audi is the only vehicle unaccounted for.

Law enforcement authorities across the country have been told to look for Cameron. In Maine, six agents from the U.S. Marshals Service, the Maine Violent Offender Task Force and local law enforcement are dedicated to the search, Knightly said.

Cameron’s decision to cut the bracelet hours after finding out his appeal was denied looks like it was made in panic, said Tracey Horton, a professor of forensic psychology and criminal justice at Thomas College in Waterville. She said that going to prison can be particularly frightening for a former prosecutor.

“It’s probably a pretty impulsive, not-very-planned-out thing,” she said. “You don’t necessarily know where you’re going to go or how you’re going to evade capture.”

Monitoring mandate

Cameron’s whereabouts were to be monitored electronically and he was required to have a land line at his home to do so, under a court order setting conditions for release.

Karen-Lee Moody, chief of U.S. Probation & Pretrial Services, wouldn’t talk specifically about Cameron Tuesday. However, she said many things can trigger an alert, her records show only one other person in the last three years cut off an electronic monitoring bracelet.

“Any time we get an alert, we have to make sure it’s for real,” Moody said.

She also said that once an alert is received from the monitoring company — national firm BI Inc. — officers verify that it is not because of equipment failure or a health issue.

“We don’t just get an alert and file a warrant (for arrest),” Moody said. “You investigate first to include sending someone to the person’s residence once we’ve exhausted the other possibilities.”

Moody said the office was aware that a three-judge panel of the U.S. 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied Cameron’s appeal, but nothing about that decision raised Cameron’s risk level.

“Every case we have is a high risk case,” Moody said. “There’s no such thing as a low awareness or low risk location monitoring case.”

Cameron was being monitored by radio frequency technology.

Moody said the office is monitoring 21 people in Maine — of those, 17 are on radio frequency monitoring and four on GPS technology.

The cost is sometimes paid by the offender and can range from $4.95 a day for basic radio frequency monitoring to $15 a day for an active GPS unit.

William Bales, a professor in the College of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Florida State University, conducted a study funded by the National Institute of Justice on the effectiveness of electronic monitoring. While that study focuses on offenders in Florida, he said in an interview Tuesday that GPS monitoring technology is more effective than radio frequency, which is tethered to a land line.

While GPS “is pretty darn effective, it’s not perfect,” Bales said. “If an offender decides to cut off an ankle bracelet and flee, we can’t control that. The alternative is incarceration, which is six times more expensive.”

However, Bales theorized that if Cameron had been on GPS monitoring and removed the bracelet, it would have been known immediately. However, “with radio frequency, they don’t know where you are every second of the day,” Bales said.

Moody said GPS monitoring is not always available in heavily wooded and remote areas. Cameron’s home in Rome is on a dirt road in woods, with Watson Pond at the rear.

Bail conditions

Cameron became the target of an investigation in 2006 and 2007 after the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children reported Yahoo! had found multiple images of child pornography in an account.

At his March 2011 sentencing, Cameron had already spent six months in federal prison, and it wasn’t kind to him. He was pale and thinner than usual, his graying hair longer and shaggier than during his 18-year tenure as a prosecutor for the state. He had to hold up the rear of his pants when he stood.

He had appealed to the court several times for release, claiming “his long-term employment as a state prosecutor … makes him extremely vulnerable in prison.”

A federal appeals court granted that wish in August 2011, ordering him freed while his convictions were under appeal and telling the trial judge, U.S. District Court Judge John A. Woodcock Jr., to set bail conditions.

The conditions included electronic monitoring, a curfew and monitoring of Cameron’s laptop by the U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services. Previously, Cameron was permitted to use the laptop to run an Internet business selling watches.

Up until last Wednesday, officers with probation services bureau said Cameron had complied with everything.

The appeals court ruling changed nothing about Cameron’s bail conditions, Clark said. He said only a judge could change those conditions and it’s not unusual for defendants — particularly in child pornography cases — to get bail pending appeal.

Clark said the court case is continuing, and the prosecutor’s office has received an extension until Dec. 28 to file a petition seeking a review by the full 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

“Right now the only problem is he is accused of violating bail,” Clark said. “The first order of business is to locate Mr. Cameron. The U.S. Marshals Service is hard at work at that.”

Clark said Cameron has not received special treatment because he had been an attorney. “I do not believe Mr. Cameron has been treated differently than any other defendant who appears in U.S. District Court,” he said.

When Cameron was indicted in U.S. District Court in Maine on 16 counts of child pornography charges in February 2009, he was living with his brother, Daniel Cameron, in Westland, Mich., a suburb of Detroit.

Cameron had been free previously on pretrial bail, sometimes in the custody of his ex-wife and sometimes in the custody of his brother.

A message left Tuesday for Barbara Cameron at her Augusta office was not returned.

After Cameron returned to Maine and pleaded not guilty at his arraignment, he was released to the custody of his brother and placed on home confinement and subject to monitoring. He was ordered to surrender his passport and not seek a new one.

In early 2010, he moved back to Maine, and a provision of his divorce allowed him to live at the Rome house.

Cameron was not assigned a custodian when bail that was set after his conviction, although the U.S. attorney’s office had requested one. Prosecutors also had asked for $75,000 secured bail — meaning he had to post that amount in money or property — but the judge permitted an unsecured $75,000 bond. With an unsecured bond, the defendant doesn’t have to post the money, but is responsible for it if he violates bail conditions.

Woodcock wrote, “To impose a requirement that the bond be secured could well frustrate the Court of Appeals’ order releasing Mr. Cameron since there is no indication that he can secure the bond.”

Staff writers Michael Shepherd and Craig Crosby contributed reporting.

Betty Adams — 621-5631

badams@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story