MANCHESTER — Part way through composing his memoirs — he’s reached the 1940s — Henry Breton decided it was time to talk about memories of serving in World War II.

“I’m doing it for my brothers,” he said. “They’d seen so much more than I did.”

The three brothers are deceased, but they all survived their military service and returned to Augusta.

Now 88 and packing for a tour of European battlefields, including the site of the Battle of the Bulge, where he served, Breton’s memories are clear and his speech retains the French accent that endeared him to the people of Belgium.

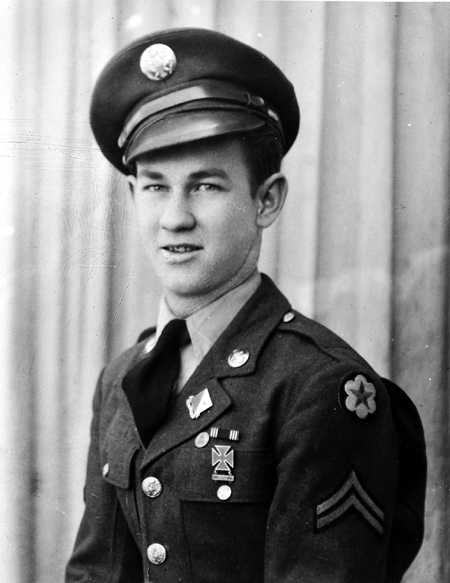

Black and white photos of four servicemen, Breton and three brothers, hang above the entryway to the family room he built last year.

The oldest of the band of brothers was Adjutor “Red” Breton. He was one of Augusta’s first draftees: “No. 158,” Henry Breton recalls.

When the draftee left the city, residents held a special sendoff for him and another soldier from Hallowell.

“They were each given a carton of cigarettes,” Henry Breton recalled. “They didn’t know they were giving him cancer.”

Adjutor Breton served in the Battle of the Kasserine Pass, the first American offensive against Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in North Africa.

The next oldest, Alfred “Norman” Breton, enlisted in 1940. He was at Scholfield Barracks when Pearl Harbor was attacked and then lost a leg fighting on the Marshall Islands. A photo in Henry Breton’s cozy basement shows a handsome, smiling Alfred raising the stump of his leg for a nurse to bandage. He died in February 2009.

The youngest brother, Lionel Breton, served in the occupation of Germany and later in Korea. He died in 2007.

A fourth brother, Doria “Jimmy” Breton, was married and had children, so he did not go into the service.

Henry Breton ended up toting a rifle even though his primary role was driver and courier for the Signal Corps in a detachment that laid communication lines at the front.

“Sometimes we were overrun by the Germans. Never mind the communications; you had to take up arms,” he said. “Waiting was the worst. Once the battle begins, you don’t think about it.”

He didn’t talk about his experiences in the service and didn’t really think about it until he started writing his own life story.

“They also say soldiers never talk about their war stories,” he said. “Actually they never talk about it because it’s a blank. I get flashes of it here and there.” Breton pulls his original Army jacket from a closet, with medals still attached, including one with three battle stars. He also has a Combat Infantryman Badge for engaging the enemy.

The jacket is still a pretty good fit. He has his cap, too.

More importantly, Breton brought home a war bride, Elizabeth Dumoulin, an accomplished pianist from Liege, Belgium, whose family didn’t want their 23-year-old daughter to marry the American GI and leave home. Breton met his wife on V-E Day, May 8, 1945, after a Belgian couple realized he could speak French and invited him to their home.

Her parents refused permission for her to wed, so the couple had to wait 30 days after a public announcement was posted. They were married at 10 a.m. on June 18, 1946, and by 3 p.m. Henry Breton reported to a Bath-made Liberty ship in Bremerhaven, Germany. (Today, that’s a 4 1/2-hour drive.) He was being shipped home for discharge.

At the docks, he rejected an offer to take his Jeep home for a $300 fee, a decision he regretted almost immediately. “I came home and I couldn’t afford a car,” he said.

Breton enlisted at 18 and proved something of a conundrum for the Army because he had already lost most of his trigger finger to a machine at the Edwards Mill.

He was sent first to cooking school, but hefting 20-gallon pots proved too heavy for his small frame.

Then he was offered truck-driving school, and that became his military career. He spent time on the Red Ball Highway, ferrying supplies to the front lines, driving a supply truck without lights at night.

After serving at the Battle of the Bulge — which began on Dec. 16, 1944, and was so named because German forces pushed their way through Allied lines in a last major counteroffensive — Breton was sent to Paris for some rest and relaxation before being reassigned to Liege, where a guitar-playing captain needed a driver. The captain had family connections to Twentieth Century Fox, Breton said, so many Hollywood entertainers stopped there on their way to put on shows for the troops.

And he recalled later bouncing around on the cobblestone roads, taking curves at top speed, wondering if his Jeep would flip and thinking, “I don’t know if I’ll make it home.” He recalls surviving on C-rations. “I ate enough of those.”

In Liege, his 31-man detachment was peppered with 88 millimeter artillery shells. The city, however, was the target of constant V2 and V1 rocket attacks, which he recalled had a high-pitched whine and then sputtered and fluttered before falling down.

“So much gas, so much distance,” he said.

Back home, he returned to the cotton mill and then went on to work at Augusta Supply, Pomerleau’s, and later had a water-proofing business franchise and Maine Billiards, finally retiring in 1989. He served as president of Le Club Calumet, Augusta’s Franco-American club, in 1964. His wife died in 2009. Their daughter, Jane, died in 2003, and he has two grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Breton is looking forward to next month’s battlefield tour of France, Belgium and Germany. “I’ll be doing the same route I did.”

Seven other World War II veterans are on the same trip and all are scheduled to receive certificates during a D-Day commemoration on June 6. “There’s not too many of us living,” Breton noted. The tour is making a special stop so he can be recognized in Liege. He’ll be visiting his wife’s first cousin, now 94.

“My wife said, ‘You’ll never recognize anything. It’s all brand new. The Americans turned the place into America,” Breton said. She visited Belgium three times after their marriage.

He disagrees, even though it has been 67 years since he’s been there.

“I spent so much time there, I’ll know it,” he said.

Betty Adams — 621-5631

badams@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story