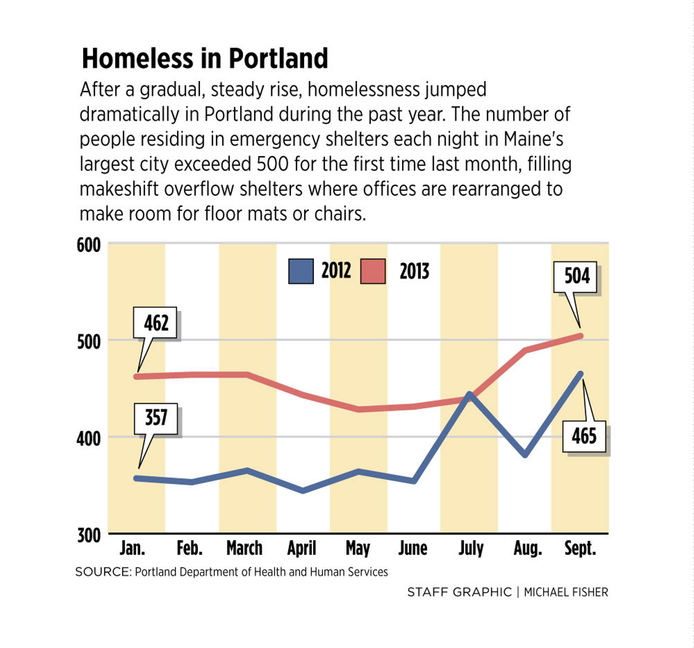

Homelessness has surged to a new, record-setting level in Portland, with more than 500 people seeking emergency shelter last month for the first time in city history.

The rise has been most dramatic among displaced families, who now overflow the city’s family shelter into area hotels at a much higher rate. But so many individuals also are overflowing the adult shelters that they are being sheltered in converted offices and sleeping on floor mats or in chairs.

The record levels of homelessness come even as many other signs point to an economic recovery. Unemployment is down slightly. Home sales are up. And a cascade of market-rate residential projects are in the pipeline for Portland’s downtown.

But the numbers at Portland’s homeless shelters tell a different story.

“People are in desperate times right now,” said Jeff Tardiff, the director of the city-run family shelter.

At the top of three flights of stairs inside a modest, three-level apartment building on Chestnut Street, a toddler welcomed visitors inside a four-bedroom apartment overlooking Back Cove as his mother sat at the table chopping vegetables and a pot of water boiled on the stove.

The apartment is an emergency shelter for families who have nowhere else to turn. Each small bedroom houses a family of up to five people, who sleep on bunk beds surrounded by practically all of their possessions.

Some of the people here are victims of domestic violence or the sluggish economy. Others lost their homes because the city condemned their apartment buildings.

An increasing number of families at the shelter are from foreign countries, either with green cards or in the U.S. to seek political asylum.

Yves Manoka, 32, has been staying at the family shelter since July 31. A native of the Democratic Republic of Congo, he came to the U.S. on a green card he received through a lottery conducted by the U.S. Embassy.

“My dream was to one day … come to America,” Manoka said.

Manoka arrived in the U.S. on May 28 with his wife and three children, whose ages range from 19 months to 11 years. The family’s first stop was Charlotte, N.C., but Manoka said his friend recommended he move to Portland because it was “a good city.”

After staying at the shelter for nearly three months, Manoka said he and his family have finally found an apartment to rent on Sherman Street in Portland’s Parkside neighborhood. Once he moves in, he hopes to find a job.

“I wish one day to be a truck driver,” he said.

FAMILY EMERGENCY

The number of families seeking emergency shelter in Portland increased 19 percent this year from a year ago, and a tight rental market is forcing people to stay longer.

The city is increasingly turning to motels as overflow shelters for families. Over the past year, the city spent more than $61,174 on motel rooms for homeless families. That’s more than triple the $16,341 spent on motels in fiscal year 2012.

Vanessa Gilliam, 34, along with her longtime boyfriend and two kids, has been calling the Motel 6 on Riverside Street home for the last several days.

Gilliam lost her job as a cashier when a fire destroyed Colucci’s market on Munjoy Hill. She had worked a deal with the landlord of her Cumberland Avenue apartment to hold onto the apartment until the store reopened.

But, Gilliam said, her former boss told her that the store was being sold and her job was not guaranteed to return, and she was forced to move out. After camping out for the summer in Limington, the cold weather swept her and her family back into the family shelter in Portland – a facility she has been in and out of a handful of times in recent years.

“We have a pretty small rug under our feet that’s keeping us stable,” Gilliam said while waiting for the school bus to drop off her 14-year-old daughter, Beverly. “Someone likes to keep pulling it out from under us.”

The family shelter is facing increased pressure from all angles. However, the biggest increase in demand is coming from newly arrived immigrants, who also typically have large families, Tardiff said.

In 2012, newly arrived immigrants accounted for only 6 percent of the families seeking emergency shelter. Now they account for 26 percent.

Seventy-three immigrant families used the family shelter in fiscal 2013, more than four times the number – 16 – that sought shelter in 2012.

While the rise in immigrants needing shelter is changing the racial makeup of the homeless population, the vast majority of Portland’s homeless population remains white. Three-quarters of the city’s homeless are white, compared to 91 percent in all other Maine communities, according to city and state data.

The sharp rise in the number of homeless families is helping drive record levels of homelessness in the city.

Last year, the city hit a grim milestone of having more than 400 people seeking emergency shelter on any given night. Last month, there were 504 people a night seeking emergency shelter, a new milestone.

Since 1987, Portland has had a policy of not turning away anyone seeking shelter. Then-City Manager Bob Ganley instituted the rule after a homeless encampment sprang up at City Hall to protest a shelter’s closing.

“That commitment has not changed and has been re-energized over the years,” said Josh O’Brien, director of the Oxford Street Shelter for adults.

To maintain that commitment, however, the city has been forced to use offices as overflow space and warming centers.

Only 272 beds, cots and sleeping mats are available each night in the six shelters run by the city and nonprofit groups. When the shelters are full, 75 additional mats are placed in the Preble Street Resource Center to handle the overflow. When that is full, an additional 17 mats are placed in the city’s general assistance office. And when that is full, people in need must sit in chairs in the city’s refugee services office.

The refugee services office was used as overflow 23 nights in September and August, during which total of 525 people sat in chairs waiting for a sleeping mat to become available.

The city recently adopted a long-term strategy to prevent and end homelessness. However, funding for some of the key components of that plan, such as rental assistance and construction money for supportive housing for the chronically homeless, has been elusive.

The ongoing budget battles in Washington, D.C., could further increase the numbers by restricting funds for federal housing vouchers.

“We’re working awfully hard and utilizing all of the resources that are available,” said Douglas Gardner, director of the city’s Health and Human Services Department.

To help reduce overcrowding, shelters are now requiring people to work with counselors to secure housing. If they refuse, they are given 24 hours to reconsider; otherwise they will not be allowed back in the shelter.

O’Brien said that 80 people have received those notices. Only two people have been suspended from shelter services, he said.

‘MOVING THE NEEDLE ON HOMELESSNESS’

Last January, Portland officials took part in the most recent nationwide point-in-time survey of homelessness.

While state data show homelessness rising in Maine and in Portland, comparable national data are not yet available. Homelessness nationwide decreased by 0.4 percent from 2011 to 2012, when a total of 633,782 people were counted as homeless, although it’s not clear if that trend continued this year.

The January survey found that 1,175 Mainers were homeless – a 12 percent increase over the previous year. But nowhere in Maine is the growing homelessness problem more acute than in Portland.

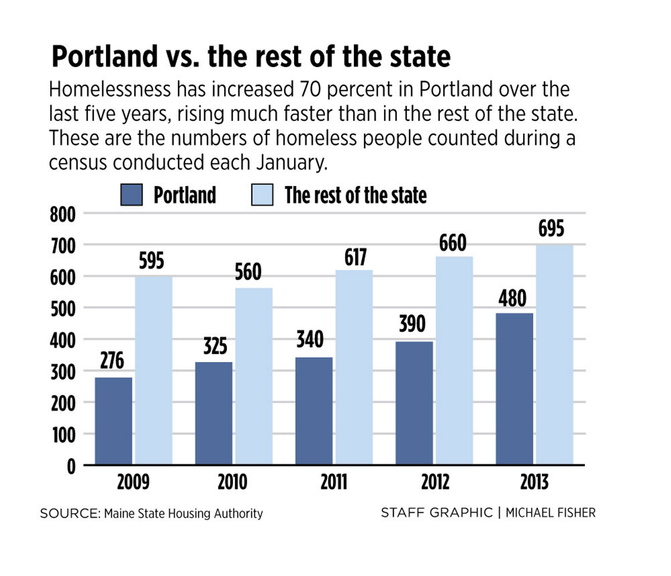

Over the last five years, Portland’s homeless population grew at a rate four times greater than the rest of the state.

From 2009 to 2013, the number of homeless people in Portland rose 70.3 percent, from 276 people to 480 people, while the rest of Maine saw a 16.8 percent increase, from 595 people to 695 people, over that same period.

Portland’s policy of low- to no-barrier services for people in need has helped make it a magnet for people seeking help. In addition to sheltering all who need it, Portland provides health care and dental care to homeless people.

Other communities in Maine, including Bangor, will turn people away at shelters for a variety of reasons, including behavioral and medical issues.

Dennis Marble, director of the Bangor Area Homeless Shelter, said that people are also turned away when the shelter’s 38 beds are full.

“By policy, we don’t take more than that, except in the winter,” Marble said.

Although Portland continues to see record-setting levels of homelessness, city officials insist they are making progress.

The city has been implementing recommendations of a 2012 study looking at ways to end and prevent homelessness, including increased availability of caseworkers, extended outreach programs, reducing barriers to the construction of new affordable housing and rehousing the newly homeless more quickly.

“We’re moving the needle on adult homelessness – we really are,” Gardner said.

In August, city officials touted a 30 percent increase in transitional and permanent housing placements, saying it has led to a decrease in the need for overflow space.

While true, those placements are not keeping pace with the need. Since that news conference, the number of homeless people in Portland has surged and the number of housing placements has trailed off.

Through September, the city had placed 520 families and single individuals in permanent or transitional housing. Already, that’s more than the 456 housing placements in all of 2012.

NO VACANCY

Even with the progress, significant challenges remain, especially when it comes to finding housing in Portland’s tight housing market.

Vacancy rates are estimated to be 3.6 percent. There is fierce competition among people who have cash to pay market rates, making it more difficult for the city to find apartments for tenants with federal Section 8 vouchers.

“Apparently cash talks,” said Tardiff, the family shelter director. “The one that shows up with cash gets the apartment.”

O’Brien, the Oxford Street Shelter director, said there are five chronically homeless people who have Section 8 vouchers still at the shelter because he cannot find them apartments. Most have special needs that must be accommodated and rely on public transportation, which adds a layer of complexity, he said.

“Factoring all those pieces in can be really complicated to find that right fit, and then overcoming the obstacle of the security deposit and application fees,” O’Brien said.

The challenge grows when trying to place families.

Over the past year, 282 families consisting of 1,011 individuals sought emergency shelter in Portland. In fiscal year 2012, 248 families consisting of 848 individuals sought shelter.

With only 94 beds available at the family shelter, the city has placed many families in area motels. Motels and hotels were used as an overflow shelter for families 198 nights in fiscal 2013. That’s up 191 percent over 2012, when hotels were used on 68 nights.

The increased demand for shelter coupled with the inability to find apartments is creating a backlog at the shelters.

Tardiff said it took three months to find an apartment for a family of 10, and he had to look as far as Biddeford for a suitable space.

There is plenty of housing available in Lewiston, where rents are much lower than in Portland, but many families want to stay in Portland, Tardiff said.

“I tell families, ‘If you’re looking to stay in Portland, it’s going to take months,’” Tardiff said.

Randy Billings can be contacted at 791-6346 or at:rbillings@pressherald.comTwitter: @randybillings

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story