BELGRADE LAKES — To the naked eye, there’s nothing wrong with the deep, cool waters of the chain of seven lakes and ponds collectively known as the Belgrade Lakes.

For most of the summer, the lakes are pristine, enjoyed by legions of summer residents and visitors who come up to swim, boat and fish in the waters nestled between the Kennebec Highlands.

But potential problems underneath the surface have local conservation groups worried about the future. A recent analysis of 40 years of water tests indicates that water quality on the lakes is on a downward trend, and if not reversed, could lead to serious water quality issues and widespread algae blooms in as few as 10 years.

A top cause of the degraded water quality is an excess of phosphorus. Despite more than a decade of work to limit the amount of phosphorus leaching into the watershed, the overall trend is still negative, according to the Belgrade Lakes Regional Conservation Alliance and other groups that have closely monitored the lakes for years.

“People are loving their lakes to death,” said Whitney King, a chemistry professor at Colby College in Waterville who has been studying the watershed for more than a decade.

In order to recommend a long-term plan, a coalition of local conservation groups launched an extensive testing program this May. The Water Quality Initiative is using weekly testing on all seven lakes in the watershed, North Pond and East Pond to the north, Long Pond and Great Pond to the west and McGrath Pond and Salmon Lake in the center and Messalonskee Lake to the east.

The project is a collaboration between the Belgrade Lakes Conservation Alliance and the Maine Lakes Resource Center, Colby College and the landowner associations on the seven lakes.

“It’s going to take everybody to fix this,” said Charlie Baeder, director of the Belgrade Lakes Conservation Alliance. “People think it looks beautiful, pristine. They don’t know there is a negative trend.”

ON THE LAKES

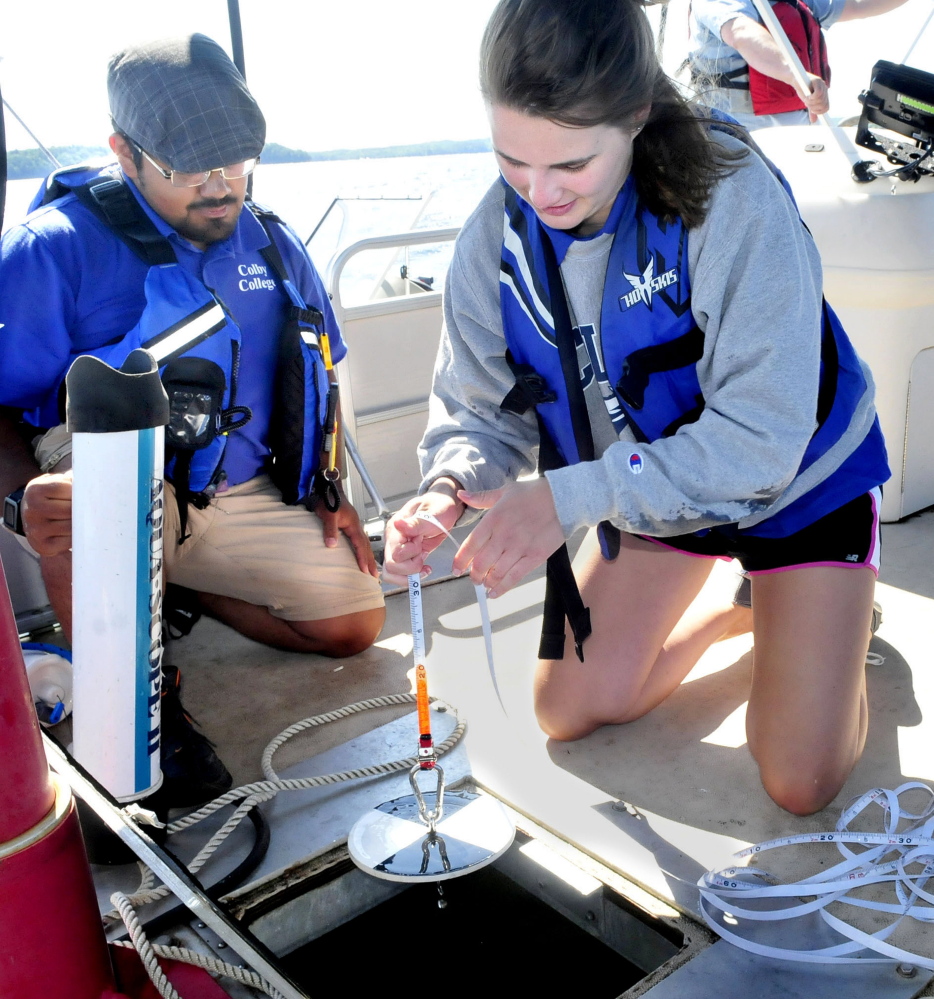

On a recent afternoon, Water Quality Initiative staff were running weekly tests from a pontoon boat converted into a floating science platform stationed on Long Pond.

Lying on the deck, Ellie Irish, a Colby College sophomore, slowly lowered a black-and-white painted disc through a hatch in the bottom of the boat. The device, called a Secchi disc, is used to record how far down, in meters, the visibility of the water is. Pristine lakes have a Secchi depth of 10 meters, while seriously impacted lakes under an algae bloom have 2 meters. According to the conservation alliance, many of the lakes in the Belgrade watershed have average depths of 4 meters.

Irish is one of seven Colby students who have been working on the initiative this summer. Along with weekly Secchi depth readings, the team uses an electronic probe to record water temperature and oxygen content. The researchers take 10 samples per meter and the results are double- and then triple-checked to ensure accuracy. The process is repeated over 10 sites in the seven lakes every week. It’s a painstaking process, but the payoff is worth it, Irish said.

“Sometimes it’s time consuming, but it gets great data,” she said.

The results are recorded on an iPad and collected at the Maine Lakes Resource Center in Belgrade Lakes by Brenda Fekete, the lake science manager. The results of the weekly tests are put online in an interactive map.

Converting the research into tools like the online map gets people engaged in the process, Fekete said. The map has been a hit, and now people look forward to the new weekly readings.

“Once you show people how to use the map, they get hooked on it,” Fekete said. The map is part of an outreach effort that includes two community meetings on July 29 and Aug. 6 at the Lakes Resource Center in Belgrade.

Researchers will also collect lake sediment, conduct bi-weekly plankton counts and measure how fast plants grow in the lakes. Denise Bruesewitz, another Colby professor, is leading an assessment of Gloetrichia, better known as blue-green algae, which has bloomed on several of the lakes in recent years.

It’s a huge effort for a good reason — an analysis of trends in lakes such as nearby China Lake, which experiences extensive algae blooms, indicate that years of mounting water quality issues led to “tipping” over to permanently poor water quality in a short period of time, three to five years, according to King. He fears the Belgrade watershed is on the same course.

“If we continue business as usual, status quo, we may get to a bloom state in the near future,” which could be as soon as 10 years, King said.

POLLUTION INCREASE

Phosphorus is the leading cause of bad water quality in the Belgrade watershed.

The nutrient supports plant life and algae in lakes, but when there is an excess it acts like a fertilizer and can result in huge algal growths, or blooms. When the algae cells die, it depletes oxygen levels in the water, and can lead to anoxic, or zero oxygen, conditions that kill off fish and other organisms. A bloom can degrade water clarity to about two meters.

In other words, if you were standing up to your waist, you couldn’t see your feet, King said.

East Pond has contended with algae blooms since the 1990s. Rob Jones, president of the East Pond Association, said the first happened following a flood in 1987 and it has been a problem ever since. The blooming fluctuates from year to year, but in general there is a small, week-long bloom in June and a longer, month-long bloom starting in late August, Jones said.

The pond association has been working with property owners in the past few years to limit phosphorus input. About 15 percent of landowners are certified under the state’s LakeSmart program that teaches homeowners strategies to reduce their impact.

“We’ve gotten to where we are by a 1,000 cuts and hopefully we can remedy it with 1,000 improvements,” Jones said.

In Long Pond, on the other hand, the impact has been long-term. A 2009 Long Pond Watershed report noted that through the 1980s, water clarity was between 6 and 8 meters on average, but by the late 1980s was at 5 to 7 meters.

Phosphorus is carried into lakes mostly through polluted snowmelt and stormwater runoff exacerbated by shoreline development like lawns and roads, as well as leaking septic systems, logging and agriculture.

For the past 15 years the conservation alliance has been working to reduce the phosphorus being added to the lakes by repairing camp roads and helping landowners limit their impact with simple solutions like growing plants to create a shoreline buffer.

Despite the efforts, water quality continued to decline. Other priorities, like controlling an outbreak of invasive milfoil, also took some of the attention away from water quality, Baeder said.

“Some people were knocking on our door saying, ‘What about the algae?'” he said.

Last summer, a group of researchers analyzed 40 years of lake monitoring data and found that anoxic periods were on the increase.

“When we did that, we realized that the Belgrades were much more impacted than we thought they were,” King said.

TAKING ACTION

The problem may be deeper than previously believed. An updated water quality assessment last year estimated that phosphorus-laden sediment, known as an internal phosphorus load, could account for 30 percent of the problem.

Internal phosphorus usually remains on the bottom, but oxygen-deprived conditions can release it from the sediment. The phosphorus is trapped underneath a band of water that separates the warm surface from the cold bottom, but when the lake temperature stabilizes in the autumn and the water mixes, that phosphorus is mixed into the entire lake.

If the internal load is the problem, the solution could be very costly, King said.

A possible treatment is to add aluminum to anoxic areas of the lakes. The phosphorus bonds with the aluminum and won’t release in anoxic conditions, which could reduce the internal load by up to 90 percent, according to King. The cost is estimated to be $1 million for Long Pond and double that for Great Pond.

Another option is to pump oxygen into the lower levels of the lake, but it is barely cheaper. King estimates capital costs could cost $600,000 in Long Pond and $800,000 in Great Pond, with annual operating costs as much as $80,000.

Back at East Pond, Jones said that the association considered aluminum treatment or oxygenation a few years ago, but decided the cost was prohibitive.

But as technologies improve, treatment might come up again as a solution. Other lakes have successfully come back from bloom conditions, Jones said.

“It’s not a one direction curve; that’s my hope and belief,” he said.

Ultimately, it will be up to the communities in the Belgrade Lakes watershed to decide how to proceed. The Water Quality Initiative team hopes to have a report with recommendations ready by this March. The team said their recommendations could be costly, but are necessary to preserve the lakes, which are an important economic driver. Tourism and seasonal employment are important sectors of the regional economy. Lakefront property provides significant local taxes.

A landmark University of Maine study from 1996 found that water quality has an effect on property values, meaning that reduced quality could mean a drop in tax dollars.

“Like it or not, we are very dependent on these lakes,” Baeder said.

On the other hand, the watershed has a unique access to resources and expertise, like Colby College and the Maine Lakes Resource Center, that can be leveraged if problems emerge, King said.

“We are poised to understand, plan and take action,” he said. “We are in a position to do something about it.”

Peter McGuire — 861-9239

Twitter: PeteL_McGuire

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story