Wade Chase sounded the alarm. He had just moved into the building on Water Street in Augusta when he was startled awake around 5 a.m. by smoke and light coming from the flames that danced just outside his door.

It was Sept. 17, 1865, and within a few hours those flames would make a relentless march down both sides of Water Street. The fire leveled nearly 100 buildings, including every lawyer’s office, all the banks, two hotels, the post office and the telegraph offices, not to mention stores and shops, bringing commerce to a virtual standstill. The New York Times’ coverage of the fire described the entire business district as “a smoking mass of ruins.”

The city on Saturday will commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Great Augusta Fire by once again closing down Water Street from Key Plaza to Bridge Street, but this time, instead of flames and terror, people will gather to remember the destruction and celebrate the rebuilding.

“We’re looking at this as an opportunity to bring people downtown and highlight a piece of the downtown’s history that a lot of people don’t know about, but that was a seminal event in the development of the city,” said Steve Pecukonis, executive director of the Augusta Downtown Alliance.

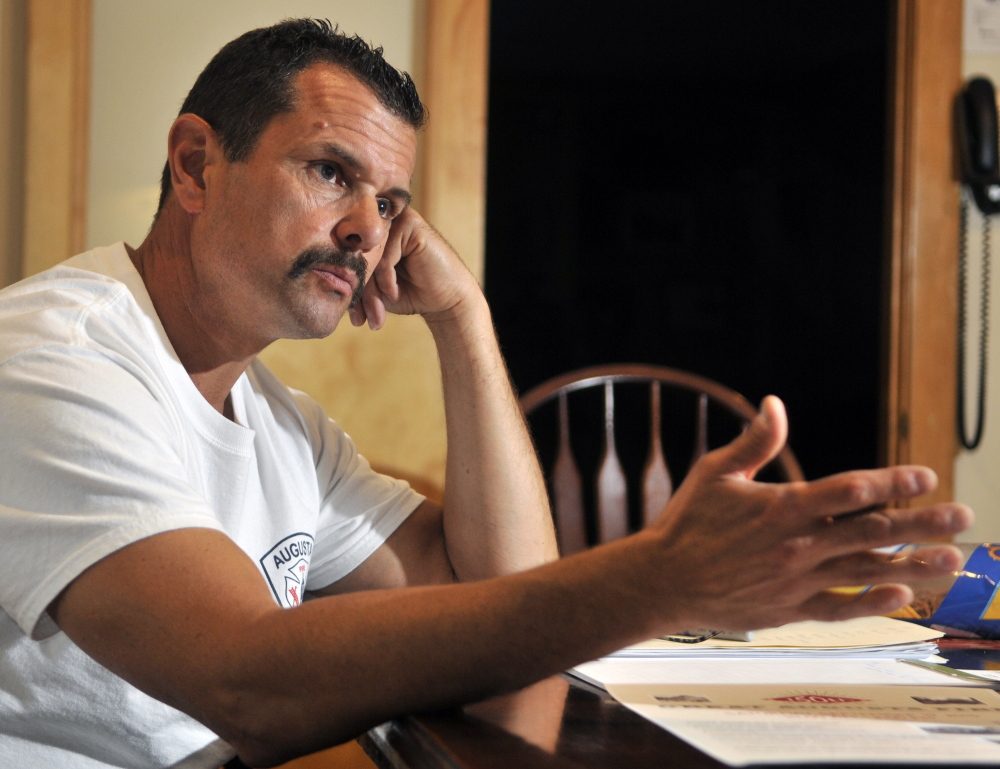

The commemoration, scheduled for 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., will include exhibits to help take people back to the 1800s. There will be 25 pieces of vintage fire equipment dating to the 1830s, said Augusta Fire Chief Roger Audette.

“There will be three pieces of equipment that actually fought the fire,” he said. “The Atlantic and Pacific from Augusta and the Tiger from Hallowell. It might be the first time they’ve been together since the fire.”

The hand tubs used to fight the fire are basically large manual pumps that firefighters, not horses, pulled to fire scenes. It took at least a couple dozen men, 12 on each side, to pump the water.

“You can imagine someone going to Hallowell to alert them and then the fire department pulling it up there and pumping it for 10 to 12 hours,” Audette said.

The Pacific is privately owned and the town of Oakland owns the Atlantic. Hallowell still owns the Tiger, which firefighters rushed from that city to Augusta the morning of the fire. “It still works,” Audette said.

DRY AND WINDY

“Great” is the adjective used to describe the fire that broke out on Sept. 17, 1865, but it is not the deadliest. As far as historians report, nobody was even hurt in the fire, Audette said. The deadliest fire in state history, in fact, occurred in Augusta five years earlier. The 1860 blaze at the Maine Insane Asylum claimed 28 lives, Audette said, and spurred the public outcry to improve the city’s fire department.

“They had one piece of equipment, and it didn’t work,” Audette said. “There was a community uproar about fire protection.”

By the time of the great fire, the city had purchased new equipment, including the Cushnoc Steamer that went into service just a month before. The occasion was marked by a large celebration in the downtown, Audette said. Nobody could have known that the steamer would be called to such important service just a few weeks later.

A combination of factors converged to create nearly ideal conditions for a huge fire. It happened in the midst of a months-long drought, and winds that day blew strong and steady off the Kennebec River, pushing the flames from building to building.

The construction of the buildings themselves, too, were ideal for a large fire. Though many were made of brick, there were enough wood buildings to give the fire a roaring start. Not only that, but the sidewalks that spanned the length of the east side of Water Street were made of wood and raised off the ground, allowing wind to fan the flames down the boardwalk like gunpowder in an old Bugs Bunny cartoon.

“The wind was not in anybody’s favor,” Audette said.

Andrew Loman, vice chairman of the Augusta Historic Preservation Commission, who compiled a history of the fire in advance of the commemoration, said Chase alerted the fire department and then helped fight the fire.

Fire Chief Eri Willis and his crew responded with the Cushnoc engine, as well as the Atlantic and Pacific pumpers. The Cushnoc was placed on Front Street, Loman said, and the Atlantic and Pacific were placed at the north and south ends of Water Street to keep the fire from spreading.

Audette said firefighters were most anxious to protect the wooden bridge across the Kennebec River that is now known as the Calumet Bridge at Old Fort Western. The bridge had been rebuilt after collapsing in 1837. The U.S. steamer Uncle Sam and the state hospital’s Deluge helped protect the bridge.

“That was a big concern, to keep it from getting to the bridge,” Audette said of the spreading fire.

James North in his tome, “The History of Augusta,” published in 1870, claimed firefighters almost made a quick stop of the blaze, but were foiled by bad equipment. City officials, citing the large expenditure on the Cushnoc engine, had rejected a request to purchase new hoses. Their frugality proved costly.

“The hoses in this line were old and weak and soon burst, and before they could be replaced, the Stanley House, Hunt’s Block and Granite Bank Building were on fire,” North wrote. “Now it was seen that the conflagration must be extensive.”

James Bradbury, who had a law office on Water Street, raced to Hallowell on his horse for help, Loman said. Hallowell responded with the Tiger. Gardiner and Pittston also brought in reinforcements, Loman said. Waterville had loaded a pumper on a train and was preparing to head south before learning the fire was out and their help was no longer necessary.

The fire made a run up Winthrop and Oak streets but was stopped by residents who soaked carpets and laid them across the roofs and sides of their homes.

“The city north of Winthrop Street seemed doomed to destruction,” North wrote.

Willis, apparently desperate to stop the fire’s progress, cut a hole in the wall of his own store and began spraying water on the flames of nearby buildings. North wrote that Willis repeatedly had to douse the fire lapping at his own house to keep the building beneath from burning out from under him.

“This act, together with the fact that one of the buildings made of granite and brick created a firewall and halted the fire, saving four remaining buildings on the northeast end of Water Street,” Loman said.

‘COMMON CALAMITY’

The fire was in check by 11 a.m., roughly six hours after it started, but the damage was done. The flames had destroyed at least 80 buildings and damaged at least 20 more. The loss was estimated at $500,000, about half of which was covered by insurance, North wrote.

“From Winthrop Street to Bridge Street, on the west side, but two posts of buildings were left standing,” North wrote. “The ground traversed by the fire was not large, but it was covered with stores and places of businesses, comprising the largest and much (of) the best part of the business portion of the city.”

The fire is believed to have been started by a disgruntled fish salesman from China. George W. Jones had sold lobsters in the city throughout the summer, North wrote. He accused soldiers of stealing some of his goods and was displeased with how police responded to his complaint.

“He became incensed and threatened vengeance upon the city,” North wrote.

Jones was believed to be responsible for a fire the night before that destroyed a barn belonging to a man with whom Jones had a dispute, North wrote. Jones went to Portland after the Augusta fire. It was there that someone damaged his fish cart and refused to pay. Jones set fire to the offender’s house later that night, but this time there was a witness. Jones was eventually arrested and “pleaded insanity,” North wrote. He was eventually deemed competent and sent to prison for the arson. He died while in custody.

The downtown business owners immediately went to work rebuilding their livelihoods. Several businesses opened up their buildings to others, even competition.

“A spirit of accommodation and friendly feeling prevailed, the offspring of a common calamity” North wrote.

That same spirit of cooperation and community exists today when a community is hit by tragedy, Pecukonis said, recalling the groundswell of support that erupted after a large fire earlier this summer in Gardiner destroyed three buildings, displacing several residents and businesses.

“People pull together after a tragedy,” he said. “It reinforces that sense of community.”

In Augusta, temporary wooden structures were erected in places, but it wasn’t long before permanent structures began to rise out of the ashes. Almost all were made of brick and granite as the city sought “a better class of building,” North wrote.

“To favor this, and to guard against the spreading of fire, the city council prohibited the erection of wooden buildings of more than a story on the burnt district,” he wrote.

The fire forever changed the face of downtown Augusta, Pecukonis said.

“Many of those buildings are the buildings you see on Water Street now,” he said.

Audette said history from across the country and here in Maine is replete with major fires that destroyed large sections of a community. There is always the impact of new codes designed to improve safety, but the other common thread is a heavy economic impact, Audette said. He said the recent Gardiner fire, which Augusta crews helped fight, is proof that the destructive blazes are not just relics of history.

“Here we are 150 years later,” Audette said. “You’d like to think when you drive through a city it will never happen again, but it could.”

Craig Crosby — 621-5642

Twitter: @CraigCrosby4

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story