OAKLAND — This year, for the first time in decades, the walls of St. Theresa Church are echoing with Latin as priests recite the liturgy to a small congregation dedicated to preserving the pre-Vatican II Roman Catholic Mass.

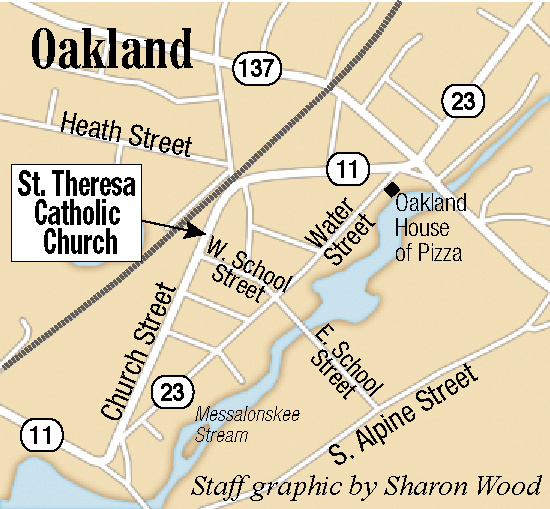

On Thursday morning about 40 parishioners, including guests from Massachusetts, Idaho and Nebraska, joined in a High Mass to bless the Church Street house of worship.

Men and women waited outside for a visiting bishop to lead them into the building. The group included a handful of visiting nuns wearing full habits.

Adhering to the church’s strict dress code, women and girls wore long, somber dresses or skirts and sweaters with long sleeves and covered their heads with loose scarves. Men wore shirts, ties, dress coats and slacks.

Inside, the congregation stood while the bishop and the priests set up the altar and walked around the room with incense, reciting verses in Latin. A chorus and organ provided music from the balcony. The blessing, followed by a High Mass, lasted about two hours.

Addressing parishioners in English between the blessing and the Mass, Bishop Mark Pivarunas, from Omaha, Nebraska, said keeping Mass in Latin was a way to connect the congregation to a “universal language” that had united the church for 2,000 years, even as it spread throughout the world.

“Everywhere in the world, people are united in one worship,” he said.

St. Theresa’s is now part of a three-church parish in New England that is part of the Congregation of Mary Immaculate Queen based in Spokane, Washington. CMRI (the initials are from the Latin “Congregatio Mariae Reginae Immaculatae”) is a sedevacantist congregation, which rejects the authority of Roman Catholic Church popes after Pius XII and since the Second Vatican Council and celebrates Latin Masses and other earlier rites of the church. The other two New England churches are in Stoneham, Massachusetts, and Warwick, Rhode Island.

The parish — Our Lady of the Most Blessed Sacrament — bought the church building from the Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland in May. Nick Isgro, Waterville’s mayor and a member of the independent church, entered into a purchase-and-sale deal with the diocese on behalf of his church.

St. Theresa was closed in 2012 as part of a consolidation of Waterville-based Corpus Christi Parish.

Over the summer, parishioners, with the help of the Rev. Anthony Short, a visiting priest, restored the building, filling in holes and giving the interior a coat of paint, moving the pipe organ to the balcony, painting the front steps and building a new altar.

“Everything you see in there is handmade,” Short said.

There are about 50 people in the parish, and the priests from CMRI’s other parishes in the Western U.S. will fly out regularly to conduct Latin masses in Oakland.

Until recently, the Oakland parish was holding services in the Cohen Community Center in Hallowell.

Parishioner Dean Bruce, of Mount Vernon, said Thursday the setting isn’t important, though.

“As long as they have the sacrament, it doesn’t matter where it is,” he said.

SPLIT IN FAITH

The worship at the Oakland church is a throwback to a more conservative Catholic tradition that doesn’t align with the contemporary church or recognize the authority of Pope Francis, the leader of the Roman Catholic Church.

After news of the church purchase was announced in May, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland distanced itself from Our Lady of the Most Blessed Sacrament.

The church “claims to be Catholic but is not in communion with the Roman Catholic Church,” the diocese said in a written statement in May. “Bishop Robert P. Deely wants to ensure that Roman Catholics clearly understand that any religious activity conducted by Our Lady of the Most Blessed Sacrament Church is not recognized by the Holy See (the Vatican) or affiliated with the Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland in any way.”

The doctrinal gulf isn’t something adherents to Latin Mass shy away from.

“They don’t want people coming to our church, because we tell people not to go to their church,” said Benedict Hughes, a priest from the Congregation of Mary Immaculate Queen, in an interview in the basement of the Oakland church after the blessing. “We don’t have a pope. We don’t recognize Francis as a lawful pope,” Huges said.

Traditional groups’ disagreement with the Vatican stems from their rejection of the significant changes in the practice of Mass that resulted from the Second Vatican Council, usually referred to as Vatican II, a series of conferences held between 1962 and 1965 that aimed to modernize the church.

After Vatican II, priests were allowed to conduct Mass in local languages and interact with the congregation instead of only following the Latin rites.

Self-described traditional groups ignore those changes and continue to worship in the pre-Vatican II fashion with the priest facing the altar with his back to the congregation, reciting the liturgy in Latin, and only interacting with the congregation to give Communion the old way by placing a wafer in the mouth of a kneeling congregant.

In a way, holding on to the previous rituals is “an indictment” of the way the church has changed in the last 50 years, Hughes said.

Pivarunas, in his remarks in church Thursday, put the division between traditional and contemporary Catholics in starker terms.

“The liberalizing, the watering down of the doctrine has brought about the apostasy,” Pivarunas said.

Pivarunas said no clearer evidence was needed than Pope Francis’ response when asked about gay priests in 2013: “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?”

Vatican experts have said Francis was striking a compassionate tone and not actually endorsing homosexuality, which the church considers a sin. Even so, Pivarunas said that statement was “like a neon sign that (Vatican leaders) have lost the faith.”

BACK INTO THE FOLD

There are traditional Catholic parishes across the world and most, like the Oakland parish, are small. The congregation has grown slowly, attracting five or 10 people a year, Hughes said.

Some American parishes are much larger, such as the group in Spokane, Washington, which has 800 people, he said.

People are attracted to the church because of its “greater sense of reverence and the worship of God,” Hughes said.

Over a potluck lunch in the church basement after the ceremony, parishioners shared their own reasons for attending Latin Mass.

Percy Doucette, 84, from Farmington, said he attended Catholic Church all his life, but the changes after Vatican II turned him off.

“I couldn’t live with what I was hearing,” he said.

He didn’t attend church for years until he found the Latin Mass in Lewiston and returned to the fold.

Dean Bruce, 74, of Mount Vernon, agreed with Doucette. The changes that ensued after Vatican II stripped the Mass of some if its rituals, and even though he had grown up attending church and going to Catholic schools, he and his wife, Irene, finally stopped attending. They tried out several other churches, including an evangelical one, but finally returned to Catholicism when they found a traditional service.

Although many of the people at the Mass were the same generation as Bruce and Doucette, there were some younger faces.

Emily Ackerman, 12, said that compared to other churches’ services she’d been to, the Latin Mass was her favorite.

“You have to wear appropriate clothes. You can’t wear pants or shorts or anything. It’s more respectful,” Ackerman said.

“I love it. All my friends go here,” she said. “I basically love everything about traditional Catholic Church.”

Peter McGuire — 861-9239

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story