AUGUSTA — Mandated shifts — essentially forced overtime — have crushed morale, driven away good workers and left workers at the state-run Riverview Psychiatric Center exhausted and worried about their families and their patients.

That’s what a number of mental health workers, nurses and other Riverview staff members told about a dozen members of the Legislature Tuesday night at a forum held at the University of Maine at Augusta.

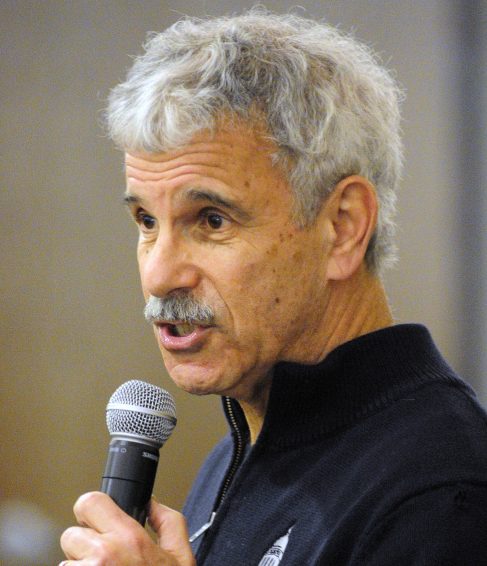

“We organized tonight just to hear from you,” Sen. Roger Katz, R-Augusta, told the 50 or so current and former Riverview workers as they sat in chairs arranged in a loose circle. “We need to get the best information we can in order to set public policy.”

He said they’ve heard from the hospital superintendent, administration, consultants and the court master who oversees a consent decree that governs how the state treats people with acute and persistent mental illness. He said sometimes the messages are confusing.

Katz started by asking, “What’s the status of things at Riverview now?” Then he and the other legislators sat and listened for more than two hours.

Laura Fisher, president of the union that represents mental health workers at Riverview, started with the problem of mandated shifts, describing some 18,000 to 24,000 hours a year in overtime.

Then there are the vacancies: 11 mental health workers, two acuity specialists and 19 nurses — all direct care staff members. She said she was told two weeks ago that 70 positions were open hospitalwide.

“There are five people that would have been here tonight, but they were mandated (to work) at 3,” she said.

Bill White, who has been a mental health worker at Riverview for 13 years, said he signs up for two overtimes every other week when he is scheduled to work to try to help out.

He said working such long shifts can be dangerous, particularly when people are called to respond to situations on the Lower Saco unit, which houses some of the most dangerous patients.

White said morale is “at rock bottom.”

“The Lower Saco special care unit is not just unsafe for us; it’s unsafe for the patients too. We’ve got some acute people,” said Shelby Moreau. She said sometimes she, another mental health worker and one nurse are staffing a unit with 14 patients on a weekend.

Dr. George Davis, a physician at Riverview, said he thinks staffing at Riverview has become more of a problem over the past decade. He offered the legislators five suggestions to help overcome it and avoid burnout for current staffers: consistent shifts for people and not mandating; staff must learn something new every day, staff must feel safe and “have the sense to have sense administration has your back,” and increase salaries to attract and keep employees.

Patrick Cote, a Riverview nurse, said he avoided mandates by working overtime. “I think I’ve mandated all of you,” he said looking around the room. He said the only thing that will fix the mandate problem is to have enough staff members. He said he doesn’t believe incentives are adequate.

Donna Bradeen, another Riverview nurse, said sometimes she also has functions as dietary aide, housekeeping and mental health worker. “There are times when we all need to share the responsibility.”

She said she’s proud to work alongside “some amazing staff members,” but acknowledged safety concerns at the hospital. “Sometimes we work with patients who just want to injure us,” Bradeen said. “They are sometimes so broken they want others to feel their pain.”

Jodi French, who worked at Riverview previously and has returned as an acuity specialist, said more mental health training is needed for new workers.

Riverview, which has 92 beds and houses people committed through the state’s criminal and civil system, has been the scene of a number of assaults by patients on staff members. The hospital has about 300 staff members.

In announcing the forum, Katz said, “We all have the same goal: a facility which provides excellent treatment for its clients and a safe and rewarding work environment for our dedicated employees. The more information we have, the better we — as policymakers — are able to do our jobs. We intend to share the information we gather with Commissioner (Mary) Mayhew and the legislative committees of jurisdiction.”

Riverview is running ads for a number of positions at the hospital, including nurses, mental health rehabilitation technicians/certified nursing aides and acuity specialists.

The acuity specialists are workers specially trained to handle patients with a history of dangerousness.

Last February the Department of Health and Human Services asked the Legislature for more money to create 30 new posts at the hospital. That was in an effort to regain certification by federal regulators and resumption of about $20 million in federal funding annually. Neither the certification nor the funding has been regained, and some of the acuity specialist posts were not funded.

At that time, figures presented to a legislative committee showed that 199 workers at Riverview had been injured in 2014.

According to the hospital’s latest quarterly performance report covering July, August and September 2015, the Riverview staff averaged more than 2,000 overtime hours in those months.

“When no volunteers are found to cover a required staffing need, an employee is mandated to cover the staffing need according to policy,” the report says. “This creates difficulty for the employee who is required to unexpectedly stay at work up to 16 hours. It also creates a safety risk.”

There were 11 mandated shifts for nurses and 125 for mental health workers in that same quarter.

In the same report, the hospital noted that as of Sept. 1, 2015, mental health workers on Lower Saco — the forensic unit to which people are first admitted and generally where the more acute cases are held — and those on Lower Kennebec, the civil admissions unit, receive $1 more per hour.

At a forum in November 2013, Riverview nurse Carlton Spotswood was among those urging legislators to pass a law to protect health care workers from violence. Spotswood’s wife was a mental health worker at Riverview who was stabbed by a patient in an incident that touched off renewed attention to the hospital’s safety procedures.

At that time, Spotswood said most other states have laws that protect health care workers from violence, some of them by instituting greater penalties for assaults against health care workers.

The federal Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services agency, which oversees Riverview funding, found numerous problems during an audit, including the use of stun guns, pepper spray and handcuffs on patients, improper record-keeping, medication errors and failure to report progress made by patients. As a result, the hospital lost eligibility for federal reimbursement of about $20 million annually. “Plans are being developed to apply for certification in 2016,” according to the hospital’s latest quarterly report.

Betty Adams — 621-5631

Twitter: @betadams

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story