WINSLOW — A 2012 response to a noise complaint in town that resulted in an officer being charged with excessive force took years and multiple court proceedings before the officer involved was cleared in a March jury trial.

Police Chief Shawn O’Leary said Monday that much of the lengthy legal tangle “could’ve been prevented” if the confrontation had been recorded.

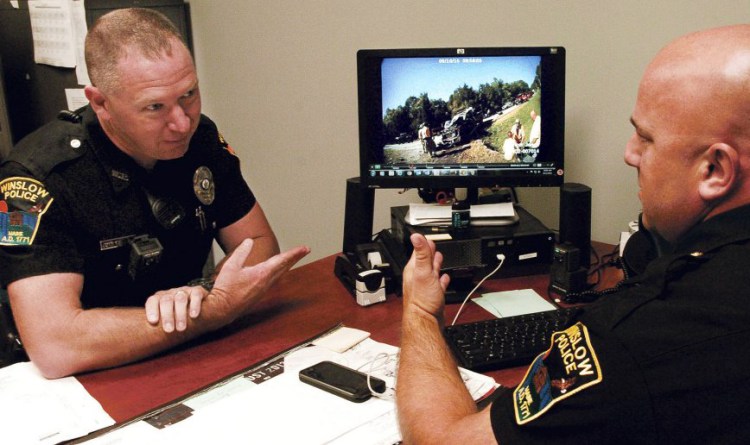

In the future, such confrontations will be. The town is the latest in central Maine to equip its officers with body cameras, and so far O’Leary and his officers say it’s been a positive move.

The department received the cameras in mid-July and began using them at the end of the month. Officers’ first impressions are positive so far, said O’Leary.

“They’ve been well-received,” he said at the police station on Monday.

O’Leary first started looking into buying body cameras for officers when Councilor Raymond Caron brought up the idea at a budget meeting. O’Leary researched the cost and technical aspects of the project before pulling together enough money to buy the units, which are about $900 apiece.

“I made it happen,” he said.

Nationwide, police departments have stepped up the move to get body cameras in the wake of controversial police shootings, beginning with unarmed teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, but central Maine towns were already choosing them as a cheaper alternative to cruiser dashboard cameras. Other area departments using them include Wilton’s, Farmington’s, Richmond’s and Monmouth’s.

A December study says that about 19 percent of the nation’s 18,000 police departments have “fully operational” body camera programs. Another 77 percent said they are either intending to implement a program or are already piloting one.

Winslow police use WatchGuard cameras and wear either a clip or a magnetized strip that the camera can attach to. The total cost to get each officer a camera was $9,965. Alternative Organizational Structure 92, the school district for Waterville, Vassalboro and Winslow, paid for half of a camera, and the department used a $2,700 grant, $1,500 from drug forfeitures and some money budgeted for supplies and other items to cover the cost.

Next year O’Leary plans to create a budget line for camera replacements, because they wear out. The costs, though, are worth it, he said.

“Times have changed,” he said. “We are being looked more upon.”

Since the Ferguson shooting and subsequent ones that have put police interactions with the public in the national spotlight, many departments nationally have invested in the cameras as a way to provide solid evidence of what happened in an interaction. In September 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice gave $20 million in federal grants to 73 law enforcement agencies to help pay for body camera costs.

Criticisms of the cameras tend to be about department policy: when they should be on and whether what’s taped on them should be made public.

Police unions in many cities and states have also opposed mandatory use of the cameras, including in Boston, where a superior court judge last week denied a request from the Boston Police Patrolman’s Association to suspend a pilot program requiring 100 officers to wear them. The program was originally voluntary, but the department moved to implement it when few volunteers signed up. The union opposed the non-voluntary nature of the pilot program.

The Winslow department has a long list of policies and procedures, which the chief compiled after researching the policies of a number of different agencies. Officers are required to activate the cameras at traffic stops, pedestrian checks, arrests, prisoner transports and other situations. Training with the cameras is also required.

O’Leary said he thinks body cameras provide police departments with a number of positives. They provide excellent evidence, hold officers accountable and also hold the community accountable for any accusations people make against police, he said, as in the excessive force lawsuit from the 2012 incident. He doesn’t see any problems with an officer being taped while on duty.

The Farmington Police Department was one of the earlier departments to get the cameras. It got them around 2008, Deputy Chief Shane Cote said. The department is on its third set of Taser-brand body cameras now.

“Officers love them,” Cote said. “They realize the cameras are there to protect the public as well as themselves.”

Cote said that even when they first started the program in 2008, “no one here was opposed to wearing a camera.”

“Everybody records everything, so we might as well record it too,” he said.

The Wilton Police Department also has body cameras. It started out with WatchGuard cameras in 2012 and now uses Taser.

“Initially, we were concerned,” Patrol Officer Derek Daley said. “There’s never a perfect call. Nobody wants to look foolish.”

But, Daley said, now they think the cameras are great. They let officers review what happened and notice things they might not have had time to take notes on.

“It would be hard for me to move to a department that didn’t have body cameras,” he said. “I think it’s a great tool.”

The videos are also used as evidence and can be useful for officers. Everything that has evidentiary value is burned onto a CD and sent to the district attorney, O’Leary said, although he wants to work on piloting a program that wouldn’t require CDs, which can get expensive. The department spends up to $400 annually on CDs, which could increase now that officers have body cameras in addition to the station’s booking camera, O’Leary said. Anything that can’t be used as evidence is stored for 90 days and then deleted.

Officers upload all their videos in the patrol room at the end of the day on a secure Waterville police server. Winslow contracts with Waterville’s information technology department for the service and doesn’t pay separately for storage. It’s covered in the annual fee it’s paid since using the service.

Storage is one of the biggest obstacles small departments have to using the cameras. The costs to store so much video securely as well as transfer video to the district attorney can add up quickly.

Police departments in Indiana and Connecticut have shelved their body camera programs after the states implemented laws requiring police to store the videos for a certain period of time. The storage costs would have largely exceeded the departments’ budgets, according to the Associated Press.

Cote said storage is an issue, so Farmington police subscribe to Taser’s secured server that allows it to share the videos directly with the district attorney, so it doesn’t have to spend money on CDs.

Madeline St. Amour – 861-9239

mstamour@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @madelinestamour

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story