WHITEFIELD — The grave marker for 6-year-old John Welch, who died Sept. 8, 1847, lay face up on the ground in the cemetery next to St. Denis Church.

Another marker standing in the same row was for Thomas, another son of Oliver and Mary Welch, who died in 1853 at age 20.

The gravestone for a 10-year-old Mallaney boy had splintered into three pieces that littered the ground. A nearby broken gravestone remarked that those buried in that plot were “Natives of the Co. Tipperary, Ireland.”

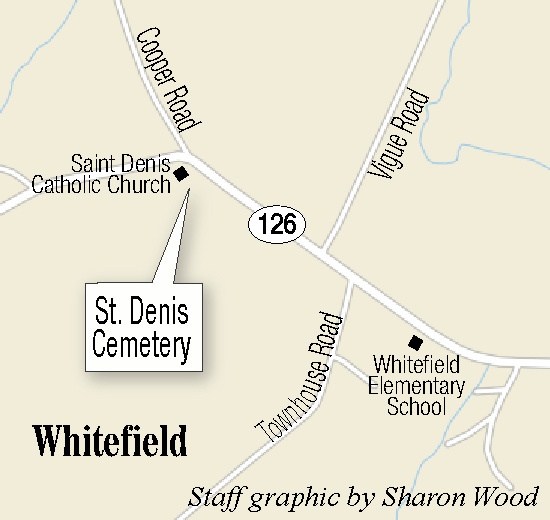

Deep ruts in the ground, plastic parts from cars and broken glass show where a Subaru Forester, sliding on its side, cut a swath through the old cemetery and tore up the gravestones nearest the mangled fence. The driver was injured and the car crash on March 27 remains under investigation by the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Office.

But the damage deeply disturbed members of the Whitefield Historical Society. Several of the gravestones belong to Irish Catholic immigrants who arrived in the community in the early 19th century.

“This is no ordinary cemetery,” Marie Sacks, one of the town archivists and an officer in the historical society, wrote in an email after a news story ran about the crash.

“It chronicles the history of Irish immigrants who began coming to Whitefield (still Ballstown) in the early 1800s. Not only names and dates, but the counties in Ireland from which the deceased emigrated are recorded here. The first gravestone dates from 1819; the last, from 1904. The 19th-century history of a community is written here: the deaths of young wives and infant children, military service, deaths by accident, memorials to the elderly erected by loving children.

“As an historian, I am grieved beyond measure by this loss.”

The top half of Catharine McGugin’s headstone was visible, but the bottom half — which lists Jan. 12, 1856, as the date she died at age 37 — was not. Probably it was among the several stones and pieces of stones lying face down in the church yard alongside the brick St. Denis Church on Route 126, also known as Grand Army Road.

A photo taken prior to the crash and uploaded to the Find A Grave website provides the missing information. Another photo on the same site shows the marker erected by her father James McGuigin, of the Parish of Dromore, County Tyrone, Ireland, to his son Thomas, who died at age 15. Many of the stones note the parishes as well as the counties of the settlers.

Sacks and fellow archivist Libby Harmon led a tour of the cemetery last week, pointing out not only the damaged stones, but others that showed the tragedy of a family that lost two daughters in 1835 — Margaret Lacy, age 29; and Bridget Lacy, age 13. Their shared gravestone carries a cross where the upright and cross pieces are of equal length. In some places that is known as the Greek cross, and Sacks says it holds meaning in Celtic lore and was adopted by those in Whitefield.

Most of the other gravestones bear the Latin or Roman cross, sometimes accompanied by the weeping willow, which Sacks said was used primarily on memorials for Protestants. Figures of lambs mark some children’s gravestones. One marker records the death of a young child at 1 year and 2 months.

There are graves of older people as well.

The earliest marker is for Elizabeth Finn, who died in 1819 at age 53.

The headstone of a child at St. Denis Cemetery in Whitefield is seen Tuesday. Several stones of Irish Catholic immigrants who arrived in the community in the early 19th century were damaged during a recent car crash that remains under investigation.

In 1995, Sacks recorded the names of 328 people listed on gravestones. “There are fewer gravestones there now than when I did that,” she said Friday.

Some of the earlier names and stones probably were swallowed up by the ground or destroyed by weather. A dozen or so smaller stones bearing initials — footstones literally placed at the foot of the graves — leaned on a fence at the rear of the cemetery. Sacks said they had been removed from the gravesites at some point (apparently to make mowing easier) and used in a patio in a private garden. The markers later were returned to the cemetery.

Sacks said the first Irish settlers came to the rural town between 1800 and 1804.

An 1811 census published by the historical society shows the population of Whitefield consisted of 510 males and 447 females.

Harmon, who attends St. Denis Church, said some descendants of original settlers still live in Whitefield.

“Tom Field is buried in that cemetery, and the Dunn family in the old Stone House on Vigue Road are descendants,” Harmon said via email. “James Keating and James Mooney are also in this cemetery, and there are descendants here in town.”

In a phone call, she added, “I know there are descendants in the Gardiner area. People in the Whitefield/Pittston area ended up going to St. Joseph Church in Gardiner.”

Some records of the cemetery are held by the Whitefield Historical Society in its home on the top floor of the Town Office on Balltown Lane. Among the collection is the May 2006 article “Maine’s Irish Community at Ballstown,” written by Sacks and published in the magazine Memories of Maine.

In it, she notes that that community grew from 13 families in 1811 to 42 in 1826.

“The Irish adjusted to the rhythms of the rural English community skillfully adapting their Irish ways of stone houses and open field single crop farming to wooden houses and the dispersed, mixed agriculture of their neighbors, although they did grow more potatoes and oats.”

Sacks said the early Irish Catholics got along with their English neighbors, which was not the case in other communities.

St. Denis Catholic Church, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was built in 1833 on the site of the original 1818 wooden chapel. The nomination paperwork, filed by the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, says the church is “the second oldest Catholic church in the state and the third oldest in New England. “St Denis Church, designed with impressive simplicity, is a monument to early Irish immigration into rural central Maine,” it says.

A Celtic cross adorns a headstone, seen Tuesday at St. Denis Cemetery in Whitefield, of sisters who died in the same year. Several stones of Irish Catholic immigrants who migrated to the community in the early 19th century were damaged during a recent car crash that remains under investigation.

Irish Catholics were attracted to the area by the presence of Rev. Dennis Ryan, a young Irish pastor, who was there from 1818 until some time in the 1830s, and the church itself is named for a patron saint of France.

Sacks said that while some of the Irish immigrants farmed, others worked in a lumber mill owned by Ryan. “He could provide work for the new arrivals,” she said. “He also bought a lot of land and resold it to newcomers. I think he did it in the interest of the parishioners.”

“To me it was interesting that (the Irish Catholics) participated in the town government,” she added. “The priest (Ryan) was on the road commission and a selectman and on the school board.”

In later years the cooperation between the Irish and their English neighbors continued.

“Around 1870 the public school was located in the convent and taught by the Sisters of Mercy, who got rave reviews from the superintendent as teachers,” Sacks said.

The brick convent building, which is across the street from the church, is still in use for various church social events and related activities.

In June, it will host a celebration of the church’s bicentennial.

The church is part of St. Michael Catholic Parish, which also has a brief history of the church’s founding and growth on its website.

Betty Adams — 621-5631

Twitter: @betadams

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story