BINGHAM — When Cathy Foran came here about 33 years ago for a job teaching first grade in a one-room schoolhouse in the West Forks, the area looked a lot different.

Quimby Middle School teacher Cathy Foran talks Wednesday about the closure of the school in Bingham. District voters decided to close the school at the end of this school year. Morning Sentinel photo by David Leaming

There were more businesses and not so many empty storefronts. There were enough students in School Administrative District 13 to have multiple classes at each grade level. Other communities — including the Forks, West Forks and Caratunk — were part of a thriving school district along the Kennebec River in central Somerset County.

Now Foran, a fourth-grade teacher at Quimby Middle School, has just 16 students in her class. And another change is in the works.

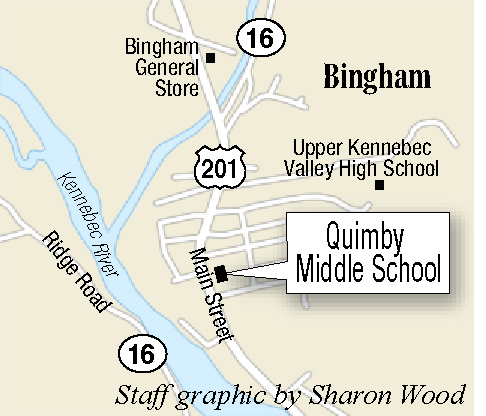

Earlier this month residents in Bingham and Moscow, the two communities that now make up SAD 13, voted to close Quimby Middle School at the end of the school year, meaning students will be redistributed to the remaining two schools in the district.

It’s a similar story in many places around Maine where an aging population has led to declining school enrollments and forced districts to make decisions about the best way to balance budgets.

“I can’t say I’m happy it’s closing, but I certainly understand why it’s closing,” Foran said. “There used to be two (classrooms) at every grade level. There were a lot of kids. Now we’re down to 46 kids in this school for three different grades.”

More than 60 schools in Maine — most of them elementary and middle schools — have closed since the 2008-2009 school year because of enrollment declines.

That doesn’t count an additional 26 schools that closed and were replaced by new construction, according to the Maine Department of Education.

The Quimby Middle School in Bingham is seen Wednesday. District voters chose to close the school at the end of the school year. Morning Sentinel photo by David Leaming

Enrollment in pre-kindergarten through grade 12 in public schools has dropped from 192,181 students in 2008-2009 to 182,496.

“Those numbers aren’t evenly distributed across the state,” said Yellow Light Breen, president and CEO of the Maine Development Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to sustainable economic growth in the state.

“Certainly rural areas have been hit harder. Some of (the school closures) are due to consolidation, but you couldn’t consolidate unless you had the room. If you have two schools built for 200 kids each and they only have 80 kids in them, then you can do that consolidation.”

In SAD 13, enrollment already has declined from 254 students in 2010-2011 to 179 students currently.

Quimby Middle School, which was built in the 1950s, when the town was still home to a thriving wood veneer mill, currently has a population of around 45 students in grades 4 to 6.

The mill closed in 1973, and with it went many of the area’s jobs.

Closing the school is something the school board has talked about on and off for about the last 10 years, though it was only recently the board voted to pass a proposal on to residents, who approved it at the polls.

The tally was 83- 71 in Bingham and 84- 12 in Moscow.

“I’m sad it’s closing, but something has to happen because we have so many less kids,” said Debbie Hibbard, who with her husband owns the E.W. Moore & Son Pharmacy on Main Street in Bingham.

Debbie Hibbard, co-owner of the E.W. Moore & Sons Pharmacy in Bingham, speaks Wednesday about the effect of and reasons for the planned closure of Quimby Middle School. District voters chose to close the school at the end of the school year. Morning Sentinel photo by David Leaming

She said a lack of jobs has caused many young people, including her own children, to move away.

“That makes sense, especially for families and children,” Hibbard said. “How are you going to support your family and children? There’s no jobs, no advancement potential, so they move.”

Superintendent Virginia Rebar said the issue of declining enrollment is what finally pushed the closure to approval. She believes it’s a similar story in many rural districts.

“There are immigrants moving into the more populated areas or cities,” Rebar said. “In fact, at a recent superintendents’ meeting, we heard there have been increases in enrollment in certain districts; but in rural areas, because of a lack of mills or larger businesses that offer employment, it’s difficult to maintain a number of schools when you don’t have the student population.”

In the nearby Somerset County town of Starks, residents and the local school board moved to close Starks Elementary School in 2010, also because of declining enrollment.

First Selectman Paul Frederic said the town has adjusted and residents are happy sending their students to school in Farmington, about a 30-minute drive away.

The school was converted into a community center that now houses town offices, but the lack of an educational center has changed the feel of the town.

“The downside is I’m not sure our children have much of a community sense, since there’s no school,” Frederic said. “We’ve overcome that to some degree by having a number of after-school, weekend and summer programs for school-age children, though; so although they might be in the Farmington or Madison school district, they do come together for some of these community functions.”

Similar discussions are also underway in Kingfield-based School Administrative District 58, which recently hosted a number of public forums to discuss declining enrollment and increased costs.

“The trend seems to be the service centers growing slightly and the rural areas are not,” said SAD 58 Superintendent Susan Pratt, who said no decisions have been made yet about how the district will move forward, and it’s possible the school board could hold off on taking any action for the time being.

“In Franklin County, that means the Farmington area is growing because that’s our service center and the outlying areas are not. It makes sense when you think about it.”

The Maine Department of Education, which previously pushed for school consolidation under the administration of Gov. John Baldacci in 2007, doesn’t have any position right now on consolidation and believes decisions on whether to close schools should be left up to individual districts, said Kelli Deveaux, spokeswoman for the department.

While some schools in Maine have closed in recent years to make way for new construction and better facilities, Deveaux said declining enrollment is also a problem.

Maine’s aging population has been well documented. According to recent U.S. Census Bureau data, the median age in the state is 44.6 years, making Maine the nation’s oldest state.

Breen, of the Maine Development Foundation, said that’s not because Maine has more elderly people than other states, but rather because young people either aren’t staying in Maine or or aren’t moving their families here.

He said as the state looks to tackle workforce challenges it’s important to maintain good health care and educational systems, particularly in rural areas.

“Economic development is not as simple as just plunking down a new business,” Breen said. “Definitely having a vibrant community is part of the whole economic case.”

Foran, the fourth-grade teacher, said she doesn’t think her students’ education will be harmed by reducing the number of buildings, but there’s still the question of what will become of the old school.

At Jimmy’s Market, the only grocery store in Bingham, former owner and founder Jim West said that’s one thing he thinks the district should have looked at more closely before voting to close Quimby Middle School, a decision that’s scheduled to take effect at the end of the school year in June.

Jimmy’s Market owner Jim West speaks Wednesday about the planned closure of the nearby Quimby Middle School in Bingham. Morning Sentinel photo by David Leaming

West, 76, grew up in Bingham. He said he’s watched the changes in the community over the last several decades.

Today, he said, his business mostly relies on tourism, including snowmobiling, whitewater rafting and other outdoor recreation that brings people to the area.

He understands young families need to go where jobs are.

“It’s not just here,” he said. “Look at all the class changes in the sports arena. A lot of A schools have gone down to B’s and B schools gone down to C’s. It’s just the way the whole state is. The population is getting older and there aren’t a lot of young people.”

Rachel Ohm — 612-2368

Twitter: @rachel_ohm

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story