LEWISTON — It took two Bates College students less than 48 hours to realize buying two teeny tiny red-eared slider turtles in Boston’s Chinatown was a bad idea.

The turtles are heavily restricted here and illegal to sell as pets in Maine or Massachusetts, though enterprising shop owners there have figured out a loophole.

“They sell them as food,” said Drew Desjardins. “You can go into the marketplace and you can buy a pound, which is a lot of little turtles, for $2.99 (for turtle soup). Or they sit outside on the sidewalks and they sell them for $25 for two because they know the American tourist market goes, ‘Oh! Those things are adorable!’ It’s easy money.”

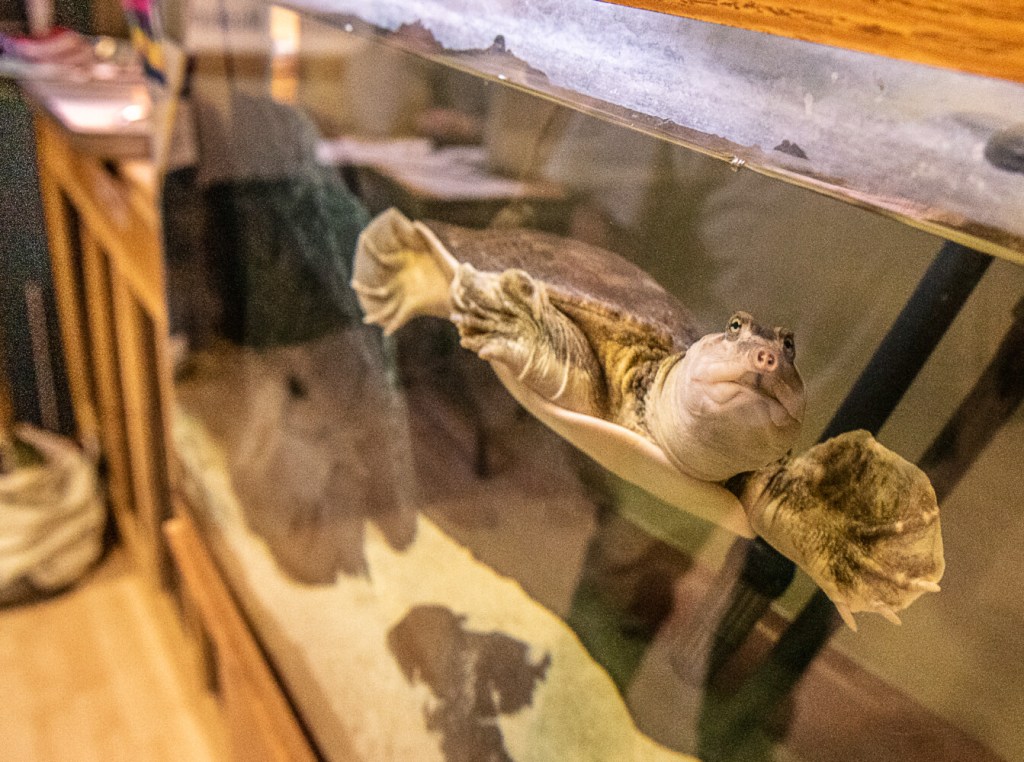

Back home after their Boston weekend, staff at PetCo in Auburn, where the students had gone for turtle food and tanks, broke the news about their illegal pets. The students quickly connected with Desjardins, who runs Mr. Drew’s Exotic Rescue and Education Center in the Pepperell Mill in Lewiston.

They aren’t the only illegal turtles there and won’t be the last — four more were dropped off in the two weeks since, two more are coming Sunday and three owners have called to see if he’d take their red-eared sliders, too.

Desjardins is the state’s unofficial, and largely unpaid, go-to reptile and amphibian guy, taking in and finding homes for about 200 dropped-off pets a year, 50% to 70% of them illegal, either outright prohibited or only allowed here with a permit under heavy restrictions.

“He’s obviously very qualified and has a great facility there,” said Nate Webb, wildlife division director at the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife. “We certainly appreciate it.”

Last week, Desjardins had two tubs in his center’s backroom filled with red-eared sliders, some waiting for a trip Desjardins is making Sunday, Oct. 6, to New Hampshire, where the turtles are legal. He brings many of the discarded pets to reptile, amphibian and invertebrate expos there four times a year hoping to find takers.

In his van, making the trip to New Hampshire: three iguanas, three Sulcata tortoises and a dozen red-eared sliders. He’d bring more turtles — 15-plus will remain at the center at least for now — but the market to find homes for them is getting too tight as more New England states follow the lead of Maine and Massachusetts.

“For the entire state, it’s basically just me,” Desjardins said. “The problem is, they’re coming at such a fast clip … I don’t want to see them released — Maine woods belong to Maine animals.”

A TURTLE OR TWO FOR THE ROAD

For decades, red-eared sliders were the most common pet turtles sold in Maine, available in stores such as Woolworths and sold with little clear, kidney-shaped pools with ramps and tiny plastic palm trees.

They can live up to 40 years, he said, and grow about a foot long.

“When they’re babies, they’re an adorable bright green,” Desjardins said. “When they get to be adults, they sort of drab right out. For some people, that’s the reason to get rid of them — they’re not as cute as they used to be.”

Maine has seven species of native turtles, four of them endangered or of concern, and in 2010 the state banned the sale of the non-native red-eared sliders so released pets wouldn’t compete for resources.

Despite the law, they are routinely released, illegally, and appear able to survive winters here.

“They’re more aggressive than our turtles — I’ve seen them do damage to snapping turtles,” Desjardins said. “Turtles, especially, you don’t see it with a lot of other animals, but with turtles, (owners) say, ‘I’m going to let it go to be happier.’ For some reason, they think if (they) let a turtle go, even if it’s not from Maine, it’s going to be happier. This is when we started seeing issues and problems.”

When the ban took effect in 2010, Desjardins said, owners were grandfathered: They could keep their pets but couldn’t trade them, sell them, give them away or bring them to a shelter.

Owners were stuck, and so, in many ways, were the state’s wardens.

Pet owners turning over a red-eared slider were upset at the prospect of it being euthanized, Desjardins said.

“So then they said, ‘We’ll have a biologist or warden or someone from the state drive them to New Hampshire,’ but then every time they’d go with a turtle or two turtles, taxpayers are going, ‘How much is he getting paid to drive a turtle to New Hampshire?'” Desjardins said. “It was a no-win — kill them or get yelled at.”

He’s accepted drop-offs since 2010, first at his home — with initial pushback from the state.

“I was told in the beginning, they’d come in guns drawn, they’ll take everything …,” Desjardins said.

The relationship turned a corner after he was invited to sit on a state committee making reptile law changes in 2016.

Having Desjardins, who holds a state wildlife exhibitor permit, be a willing option gets wardens out of that no-win, kill-them-or-drive-them-away bind, said Webb, with MDIF&W.

“It does give us a way to take in the animal and bring it to someone who has the capability and is actually permitted to hold those animals,” he said. “It’s a huge benefit to us, certainly.”

NEW HAMPSHIRE LEGAL

Broadly speaking, Maine has three categories when it comes to having wildlife as pets: Allowed, absolutely no way and potentially allowed, under restricted circumstances, with a permit.

On the 18-page unrestricted list: A Chilean rose tarantula, Cairo spiny mouse, flap-necked chameleon, leopard tortoise and Sonoran mud turtle, along with thousands of others. A recent addition that Webb said once triggered a lot of calls: Hedgehogs.

“It used to be a species that a permit was required for,” he said.

Among those limited to exhibitors, animal rehabilitators and research centers, with a permit: African clawed frogs, crocodiles and red-eared sliders.

The lists for both, allowed and tightly regulated, go on and on.

The list of prohibited animals, on the other hand, is surprisingly short: Mute swans and monk parakeets.

When it comes to keeping restricted or prohibited animals out of Maine, it doesn’t help that so many are sold just across the border.

“New Hampshire has no regulations, so it’s nothing to be on a day trip, ‘You know what? I haven’t seen one of these in years, I’m going to get one,'” Desjardins said. “The pet store in New Hampshire is not going to sit there, ‘Excuse me, are you from Maine?'”

Easily found there, he said:

• Monk parakeets, also known as Quaker parrots, are agricultural pests.

“They’re a colony breeder so one nest can weigh over 800 pounds, so it makes the tree incredibly top heavy,” and dangerous in a fall, he said.

• Sulcata tortoises, restricted here, can “live 150 years,” said Desjardins. “Maine says ‘What are you going to do with an animal that lives longer than you? They get to 200 pounds.’ People’s response is, ‘I’ll just will it to my kids.’ You don’t know your child’s future, you don’t know your future.”

• Axolotls, restricted here, are “super cute” Mexican salamanders.

“Everybody in Maine wants one, including you, you just don’t know it yet,” Desjardins said. “That was probably the longest thing we discussed (during the 2016-2017 rule change meetings); the state was firm in saying no.”

There’s the risk they could spread disease and compete for resources if released.

Illegal pets end up in Desjardins’ care via boxes at his door, donations on the road while he’s at shows and after anxious calls like the one from the Bates students.

“They were very nice about ‘Thank you, you’re a godsend. We didn’t know and we feel bad,'” Desjardins said. “They could have released them in Andrews Pond in Bates.”

Keeping that tiny pair out of the wild, though, comes with a cost: “These two have become a problem because the federal law states they have to be over four inches (to be rehomed), so I can’t do anything with them unless I’m giving them to another educational institution,” Desjardins said. Turtles grow about an inch a year, “so you’re looking at three, four years before I can move them out.”

After getting hundreds of hits on a Facebook post about the two turtles last month, Desjardins said some people donated money to ship them out of state and Maine horse owners planning future trips out of state volunteered to transport his animals to new homes along the way, lessening his burden.

“Now I’m setting up this network,” he said. “There’s only so much you can get rid of in New Hampshire; my markets are getting saturated. I need to go to their native range where they can be released.”

For a drive, there’s gas and his time. Mailing an animal overnight can cost up to $200, he said.

Desjardins estimated it costs more than $10,000 a year to care for his menagerie, a mix of dropped-off animals and the center’s 150 permanent residents, all of which came to him through different circumstances — illegal drop-offs, abuse, neglect and owners simply not able to care for their pets anymore.

Though MDIF&W sends people his way, Desjardins is paid by the state only when he’s caring for an animal involved in a pending court case. The Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry recently paid him $1 a day per turtle to watch four turtles in a seizure case.

He’d like to see more signs and more education around which pets are allowed in Maine and which aren’t.

Someone moving here from California, “there’s no signs coming into the state telling them your pet might be illegal,” Desjardins said.

“I don’t own a boat, I don’t have a trailer, any of that stuff, but I know if I go to a boat launch and I take my boat out, I need to check for plants,” he said. “I don’t have to worry about firewood, but I know if I come into Maine with firewood, that’s illegal. It’s on radio, TV and print. It’s (on) a sign coming into Maine. There’s nothing for education on pets. It’s basically ‘Check our website’ — nobody thinks of that. The state needs to step up.”

Webb said staff hear daily from the public asking about the laws and what they can possess.

“One thing we are working on is just making the general public aware that there’s a list of species that people can possess without a permit, but for everything else, they’re not available for private ownership or possession in people’s homes unless they go through a permitting process,” he said.

“It effects the general public at large in Maine — that can be a challenge to communicate something at that scale, but we are working on increasing those efforts as time goes on,” he said.

Current red-eared slider owners, he said, should contact MDIF&W to start the permit process to possess it legally, with the aim of making sure it’s never released to harm native wildlife.

While the state’s education efforts scale up, avoid adorable Chinatown turtles. And take this advice from Desjardins, who has a long-term goal to create a Family Museum of Natural Science in Lewiston: “Before you buy, I’m a free resource — just reach out, talk to me.”

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.