FAIRFIELD — Deborah Staber has been the director of the L.C. Bates Museum for more than 30 years. She can’t remember a time when there wasn’t some sort of renovation or preservation work going on at the museum.

Staber describes the museum as “one of the last remaining collections of cabinets of curiosities in America.” Within the building is an elaborate maze of glass cases and shelves containing everything from taxidermized animals and embalmed tree trunks to rare crystals and century-old dentistry equipment.

Izaac Alderman with Larsen Masonry uses a brush while repointing the walls for paint Monday in a display space at the L.C. Bates Museum at Good Will-Hinckley in Fairfield. The room contains wagons dating back to the late 1700s and printing presses from as early as 1832. The building, built in 1911 in the Romanesque Revival style, is undergoing restoration while being historically preserved, according to museum director Deborah Staber, who has been with the museum for 32 years. Rich Abrahamson/Morning Sentinel

In addition to the ongoing effort of preserving its extensive collection of natural and human history, Staber says the museum is always working to preserve itself, too.

The museum, located in the Hinckley neighborhood of Fairfield, recently began work to renovate its roof, repair its exterior brickwork, revitalize its exhibits and more, which Staber said is part of a constant effort to maintain the building.

“We’re trying to restore the building and treat it as an artifact too,” she says. “We’re constantly working on it. Everything is a long-term project.”

The building and museum first opened in 1903, Staber said, and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987.

Because of the museum’s age and its historic status, any renovations or repairs made to the building must be done as carefully as preservation work to its exhibits, Staber said.

Whether to the building or the museum’s exhibits, all work must be approved by a professional conservator. Any repair work must be done to the building’s original specifications, Staber said, or else it loses its recognition as a historical building.

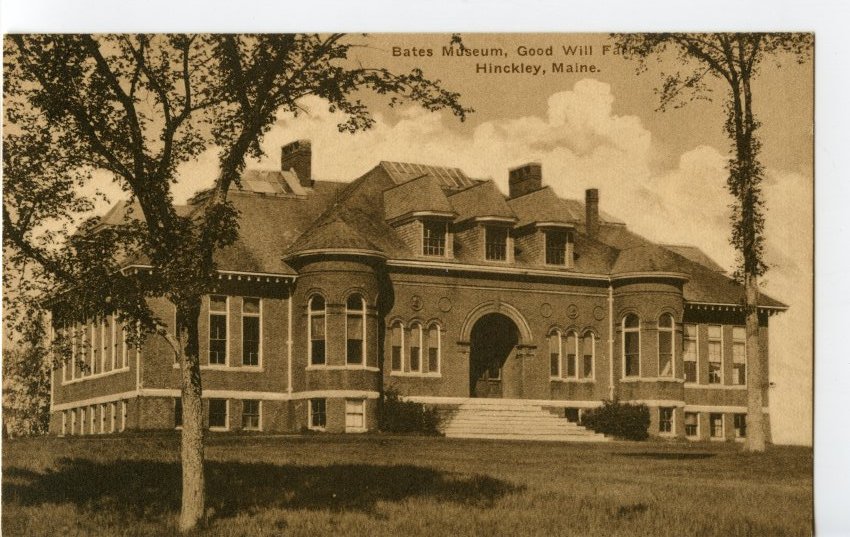

A historic photograph shows the 1903 Romanesque Revival L.C. Bates Museum Building designed by architect William Miller. Contributed photo

Instead of using cement or modern tools to repair the building’s brickwork and masonry, the museum is making repairs with original bricks from the early 1900s. Rather than just replacing the glass panes in the building’s windows, workers must also entirely remove, rebuild and replace the wooden frames around them, too. Special stones and tools must be used to cut and lay masonry work around the outside of the building.

“We’re working on preserving the structure of the building, and it all has to be done in a very particular way,” Staber said. “We’ve been redoing the windows, whitewashing the bricks, doing work on the roof. Lots of little and big processes.”

All renovation work at the L.C. Bates Museum is funded through a combination of federal and state grants. Though Staber said it was difficult to estimate the total cost of the current spate of repair work, she said the intensive nature of making historical preservations often makes it more expensive to do and harder to find qualified contractors.

While repairing a normal window may only cost a few hundred dollars, Staber said each of the museum’s replaced windows costs around $3,000.

Though the museum has hired out professionals to handle most of the exterior repairs, much of the interior work is done by a small, tight-knit group of volunteers.

Michael Hofmann estimates that he has volunteered at the L.C. Bates Museum for five or six years now as a self-described jack-of-all-trades. He’s done everything from building glass cases for taxidermized owls to painting and repairing original pieces of the museum’s architecture.

Colby College student Sarah Byrne catalogs a historic seed collection Monday while sharing a workspace with a saddle billed stork that is part of the collection of the bird mounts at the L.C. Bates Museum at Good Will-Hinckley in Fairfield. Museum Director Deborah Staber says the building is undergoing restoration while being historically preserved. The museum was built in 1911 in the Romanesque Revival style. Rich Abrahamson/Morning Sentinel

He said working at the museum is not unlike being one of the hundreds of schoolchildren who visits it each year.

“I’m learning as I go. We all are,” Hofmann said. “I learn new ways to fix and repair things. I research the collections we have. There’s just so much to learn here.”

Hofmann, like Staber, said he mostly started working at the museum by accident.

“There was a little ad in the newspaper, it said, ‘We need somebody to put together some shelving racks,'” Hofmann recalled. “I thought, ‘This is going to be a one-off,’ and went. I put together 30 more storage racks and I’ve stuck around since.”

Staber know she will not see the end of the renovation work, not just because repairs are always ongoing, but because she is stepping away from the L.C. Bates Museum in September. She has been the museum’s director since 1992 and says keeping it alive has helped give her a sense of purpose.

As the museum celebrates the 100th anniversary of its first taxidermized animal exhibits, Staber hopes that the renovation work now will help keep one of the country’s most unique and eclectic museums thriving through the next 100 years.

“There are very few museums left like this. It isn’t all plastic signage and traveling, rotating exhibits,” Staber said. “A lot of things have changed, but the museum is still here.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Modify your screen name

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.