It was a battle for Saco’s future. On that point, everyone seemed to agree.

On Oct. 4, 2022, a Maine homebuilder named Loni Graiver stepped in front of the Saco planning board and pitched his vision. He promised the Lincoln Village housing development would bring new opportunities for young couples and retirees, new municipal tax revenue and new dollars flowing into the pockets of local businesses.

Graiver said he was motivated by purpose as much as profit. He felt the 288 condominiums at the heart of the project were just what Saco needed to combat a housing shortage that has made homeownership seem like a near-impossible dream for a generation of Mainers.

Then the neighbors took the floor.

“This will be devastating for the area,” one resident said.

“This is a great development. It’s beautiful,” another said. “But I really don’t think it belongs.”

So began a yearslong trench war, fought month after month in marathon planning board meetings, over social media posts and, eventually, courtrooms.

The battle left few satisfied. Not Graiver, whose project was ultimately rejected and whose land still sits empty. Not the victorious neighbors, who believe they had to overcome the bias of local officials to save their neighborhood. And not several people currently or previously involved in Saco municipal government who told the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram they worry the anti-development rhetoric will drive builders away from the city.

The defeat of Lincoln Village is just one example of a pattern that has played out time and time again in Maine: A developer tries to build the dense, more affordable housing that experts say is necessary to overcome the state’s stubborn crisis, only to face fierce opposition from a small but vocal group of residents who like their town the way it is.

Watch: Saco resident Abby Villarreal opposes the Lincoln Village project during an Oct. 2023 planning board meeting. The board rejected the proposal later that month.

And if members of the public can convince their planning board that a project is wrong for the community, municipal zoning ordinances are weighted in their favor. So, too, is legal precedent.

Similar scenarios played out last year in Cumberland, where residents overwhelmingly rejected an affordable housing proposal after the town sent the matter out for referendum, and in Auburn, where a developer abandoned ambitious plans for a housing development after local residents rose up in opposition and elected a new mayor whose campaign was built around fighting the project.

Alex Horowitz, a housing policy expert at the Pew Research Center in Washington, D.C., said when development decisions are made on a building-by-building basis by mostly non-experts and often unelected planning board members, it opens the door for opponents to wield outsized power.

“Land use decisions made at the local level, exclusively, for a long time, without a clear set of guidelines from the state, is what has resulted in our large housing shortage,” he said.

Listen: During a June 2023 planning board member, Saco resident Dan Laskey asks members to reject a housing development proposal for a parcel of land near downtown.

Saco City Councilor Michael Burman, one of few officials willing to talk openly about Lincoln Village, said he understands why people who love their neighborhood would want to avoid disruptive change, and said some of the concerns raised by opponents were valid.

But given Maine’s rapidly aging population and difficult housing market, are staunch opponents of development preserving their communities or sucking the life out of them?

THE DEVELOPER

Graiver bought the 56-acre parcel about a mile west of the center of town in late 2021 for $1.5 million cash.

The initial idea for Lincoln Village was to divide the land into 80 single-family lots. But as Graiver talked about it with city staff, he concluded that wasn’t what the market needed.

“Saco is filled with $600,000 to $800,000 single-family, 2,200-square-foot McMansions,” he said.

So, he modified his plan to create 288 condos that would be priced in the high $200,000s to mid-$300,000s, along with a few dozen single-family homes and townhomes. He envisioned the target market as first-time buyers and those looking to downsize.

That type of new housing is relatively rare. A 2023 report by the state’s housing authority concluded Maine needs to build 84,000 homes by 2030 to correct an existing shortfall and meet expected population growth. That can’t be done with small, single-family subdivisions alone.

Saco, like many communities, has felt the pinch.

“We have a real housing crisis in Saco that’s largely tied simply to a lack of supply,” Burman said. “People who were born, raised and grew up in Saco simply can’t afford to buy in Saco at this point.”

On paper, the Lincoln Village property had several of the elements seen as crucial to a successful housing development, Burman said — preexisting access to city water and sewer services, proximity to a grocery store, a pharmacy, and locally owned businesses downtown.

But there were warning signs, too.

When Graiver bought the land, he knew that the previous owner, John Flatley of Nashua, New Hampshire, had tried to develop seven apartment buildings with 48 units each on that site. The planning board rejected it within two months, following ferocious opposition from neighbors.

Instead of modifying his plan and trying again, Flatley opted to sell. He didn’t respond to multiple messages for this story.

Developer Loni Graiver lost an opportunity to develop a 56-acre parcel in Saco when opposition from the community outweighed the need for housing. Daryn Slover/Portland Press Herald

Yet even though that project had sparked outrage, Graiver had two things going for him that Flatley did not. He’s a Maine-based developer of more than 20 years, and he wasn’t asking for any special zoning conditions.

“I wasn’t expecting to have a red carpet and parade, you know, and a statue of me in front of the subdivision for being a hero for taking this on,” he said. “But I did expect a lot more common-sense people who could see this was a cool product that could help solve a lot of problems.”

Looking back, he admits he underestimated how loud the residents would be, and how much influence they would have.

THE OPPONENTS

Groundwork for the opposition to Lincoln Village was laid years before the project was conceived.

Inga Browne, a transplant from upstate New York, first got involved in city affairs in the early 2000s when she formed a community group to fight Saco’s plan to demolish a historic stone bridge near her home and replace it with a standard culvert.

The group’s concerns went beyond just the bridge’s history. Members worried that new development and outsiders moving in would not only damage Saco’s character but jeopardize federal funding the town receives by raising property values.

Inga Browne, a leader of the Save Saco Neighborhoods group, walks past a blue survey ribbon in woods off Maple Street in Saco where the application for a 332-unit development, the Lincoln Village development, was denied by the city after the developer received a preliminary approval. Gregory Rec/Portland Press Herald

Browne’s campaign was successful. Saco voters approved a $990,000 bond in 2014 to pay for improvements and reopen the bridge to traffic.

“That was how I cut my teeth with Saco’s municipal process,” she recalled. “Going to council meetings, meeting with public works directors, emailing people, all this stuff.”

When the Flatley project was first proposed, Browne planned to galvanize public support using that same playbook. But her knowledge of Saco’s government and a platform on social media helped her campaign move much quicker.

Save Saco Neighborhoods’ Facebook page was created in January 2021. By late February, it had nearly 1,000 followers. Dozens and dozens of residents spoke out at public meetings against the project. The group attempted to recall a member of the City Council who they believed to be sympathetic to the project, prompting his resignation. By March, the Flatley effort had been soundly defeated and the developer put the parcel up for sale.

“So, when the Lincoln project unfolded, I had already been around the bend a bit,” Browne said.

As soon as Graiver filed preliminary plans for the project with the town in April 2022, Save Saco Neighborhoods began organizing. Within weeks, dozens of residents were swamping public comments, yard signs began dotting front lawns and social media posts opposing the “city within a city” spread through the community.

At the first public hearing in October, 17 residents testified against the project.

There was Chelsea Hill, who moved to Saco from Michigan just one year before the project was proposed. She, too, had concerns about its size and scale, but safety was top of mind. Her son had brought home from school a book with sticker that memorialized a 7-year-old who was hit and killed by a car in the neighborhood nearly 20 years earlier.

She immediately broke down in tears.

“He was my son’s age. I just thought ‘This is a sign,’” Hill said. “It made me feel like I had to speak up.”

Listen: Saco resident Dimitra Voulgari outlines her opposition to the housing proposal during an October 2023 planning board meeting.

Tom Klak, a Saco resident and professor at the University of New England, said the parcel of land was home to a “significant” number of chestnut trees, which are in danger of becoming extinct because of fungal blight. He said that’s reason enough to keep the land undeveloped.

“Obviously there’s a need for housing — we can’t forget that. But there’s also a need for protecting nature,” he said. “We can’t develop everything.”

Many of those same neighbors returned when the board took the issue up again the following spring. They complained that there was no room for new children in Saco’s school system, that Gravier’s condos wouldn’t fit with the rest of the neighborhood, that they weren’t even really all that affordable.

Over a dozen meetings, many residents spoke out six or more times. Some said they supported the idea of building more housing in Saco — just not this housing. Not here. Not now.

VOTE CONFUSION

By June 2023, it was clear that the group had sympathizers on the planning board, especially when it came to the issue of traffic.

At the planning board’s preliminary vote on the project, three out of six members agreed with the public and said that Graiver’s team had failed to prove that the project would not “cause unreasonable highway or public road congestion or unsafe conditions.”

The tie vote was a loss for the developer, and by falling short on just one of the 20 conditions listed under Saco’s subdivision review rules, the project failed the entire review. Lincoln Village was dead.

Or it would have been, if the three board members who voted “no” on traffic had provided evidence to justify their decision. But that proved surprisingly difficult.

Under Maine law, planning board members are forbidden from judging a proposal based on whether they personally like it, or even whether they think it would be the best thing for their community. Instead, they must determine whether a project objectively meets the criteria set by local statute, and — if they want their decision to survive an appeal — they must point to evidence that backs up their decision.

Jeff Grossman said common sense drove his vote. Everyone knew that traffic was already lousy in the area. Obviously adding hundreds more cars would just make it worse.

Traffic on Bradley Street in Saco on April 2, near where a large development was proposed. Neighbors’ concerns over increased traffic in the area is one of the reasons the development proposal was rejected by the city. Gregory Rec/Portland Press Herald

But City Attorney Tim Murphy warned that “common sense” might not stand up in court.

Diane Morabito, a traffic expert hired by the city to review the project, had been persuaded that Graiver was doing enough to mitigate traffic that it wouldn’t be a problem.

“She is on record that this is the most traffic mitigation that she’s ever seen for the type of traffic count we were producing,” Graiver said.

The Maine Department of Transportation had come to the same conclusion, and had granted the project a traffic movement permit, which in Graiver’s experience had been a “golden ticket” for developers.

Grossman suggested that the board could rely on the hours of public testimony from residents, including Hill, who had spent months learning the basics of traffic science, conducting her own counts of cars and trucks passing through the neighborhood, and engaging in occasionally testy email exchanges with the state’s own traffic experts about the flawed methodology of their studies.

But again, the city attorney questioned whether a judge would value citizen testimony over the word of several experts.

Two of the dissenting members eventually concluded that their hands were tied and reversed their vote. The board granted the project preliminary approval.

Graiver’s vision remained alive. But the opposition was more energized than ever.

DECISION REVERSED, THEN APPEALED

As the plan inched toward final approval, residents became convinced that city staff were biased or incompetent for siding with a for-profit developer instead of the people of Saco.

The group collected 172 signatures for a grievance petition accusing some Saco planning board and other city staff of having a conflict of interest and of failing to follow appropriate procedure during its deliberations.

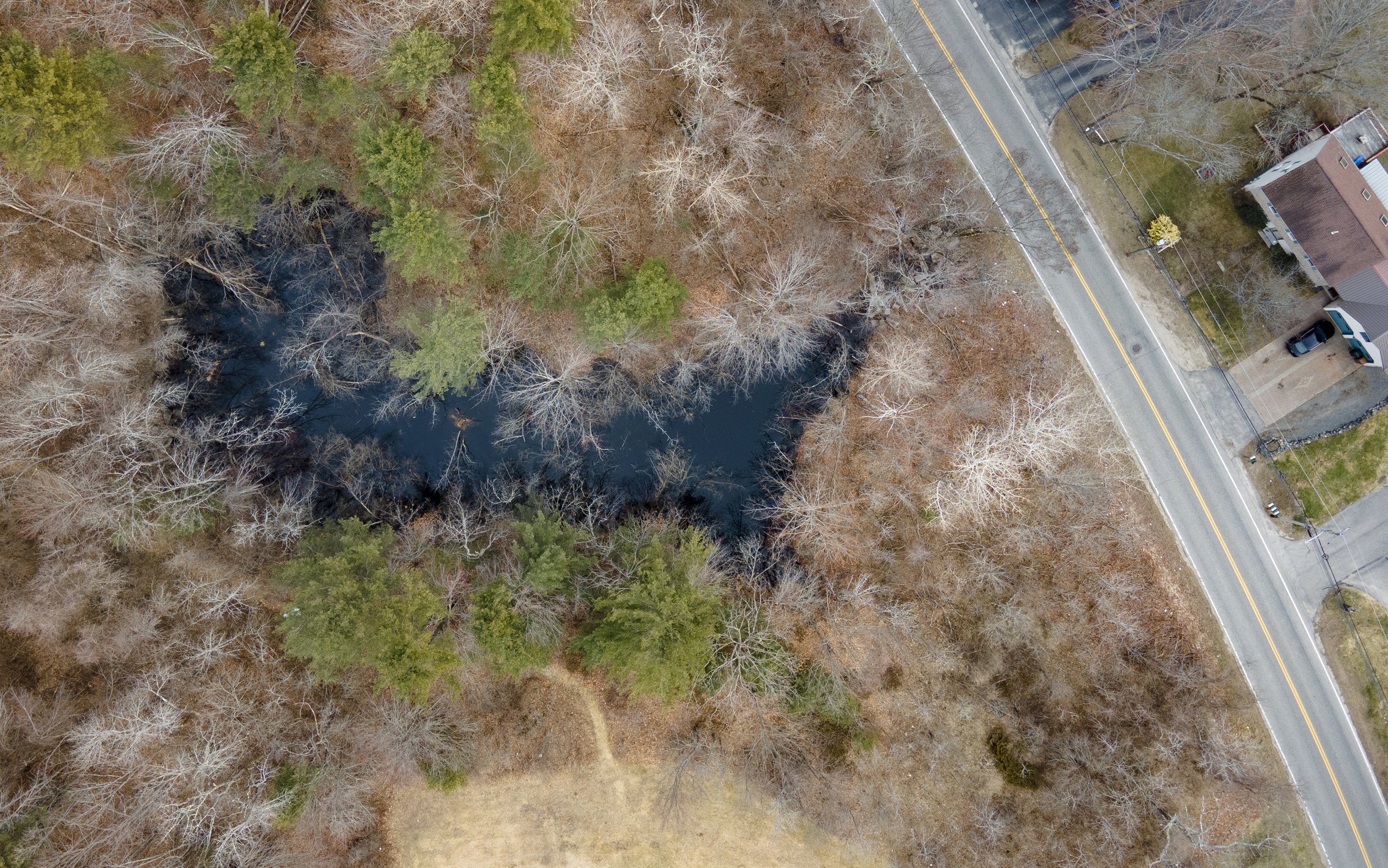

An old quarry in the area between Lincoln and Bradley streets in Saco, where neighbors successfully stopped a large-scale development. Gregory Rec/Portland Press Herald

The petition prompted a special meeting before the Town Council in September 2023. For two-and-a-half hours, residents stepped up to the podium and expressed their outrage at what they viewed as the town’s attempts to silence them.

“This is an endemic corruption that we have in the city of Saco,” one resident said. “We have to stop ignoring, circumventing, violating or breaking the state and local laws.”

A month later, the board voted a second and final time on whether Lincoln village met all 20 subdivision review standards.

The project hadn’t changed much since the spring vote. Neither had the standards. But this time, the board found reason to vote against the project on five separate criteria, including two that in June had been unanimously approved.

After more than a year of intense effort — of hours and hours of researching municipal codes and emailing traffic experts and testifying at public meetings — the residents had finally gotten their wish.

Graiver was stunned.

He’d never heard of a project that was rejected after it won initial approval.

“If there was a fear that this panel could completely reverse themselves, who in their right mind would spend all these extra hundreds of thousands of dollars between preliminary and final approval? We would all lose faith in the system,” he said.

Graiver appealed the decision as arbitrary and “unsupported by evidence.” It was heard by a judge in Maine Business and Consumer Court.

Several developers and real estate professionals wrote letters of support.

“Never in all my years of watching developers jump through planning board hoops, have I witnessed such obviously political and unprecedented review with a reversal of a preliminary approval,” said Bill Bridges, of Raymond.

The appeal process dragged out for nearly a year, but in the end a judge ruled that Saco’s planning board is not bound by its factual findings in an application for preliminary review when making a decision on final subdivision approval. In short, the board could change its mind, and the denial would stand.

Of the five criteria the board voted against, though, the judge found that only the part about traffic would hold up.

“The court appreciates that the evidence presented by the developer and the peer-reviewed expert may be better in quantity and quality than the evidence relied on by the board,” Justice Thomas McKeon wrote. “The court, however, can neither weigh evidence nor weigh policy considerations. Instead, the developer had the burden to persuade the board.”

An aerial view of an area between Lincoln and Bradley streets in Saco, seen in the top half of this photo, where neighbors successfully stopped a large-scale development. Gregory Rec/Portland Press Herald

AFTERMATH

The Saco example demonstrates that when community members organize to fight development, they can often have outsized power, according to Horowitz, the housing policy expert with Pew Research.

“I think the idea is that there is supposed to be a set of rules and everyone follows,” he said. “So, there is a real sense that when projects are debated on a building-by-building basis, that undermines fairness.”

Horowitz said that even well-intentioned town planning officials might not always be making decisions objectively.

Indeed, some elected officials were publicly supportive of Save Saco Neighborhoods.

Phil Hatch was a member and “unofficial spokesperson” for the group in 2021 when the first housing proposal was defeated. Only a month later, he was appointed to fill a City Council seat that was vacated by a recall. Hatch served on the council while the Lincoln Village project was being decided.

“I resigned all of my connection to the group when I was sworn in on April 15, 2021,” Hatch said. “And it’s my own personal professional training, my own personal integrity, my own personal desire to do what’s right that leads me to do these things.”

Hatch did speak in opposition to the project during at least two meetings, although he said he did that as a private citizen. He lives in the neighborhood near the proposed development.

Likewise, planning board member Robert Biggs lived in the neighborhood and was a member of the Save Saco Neighborhoods Facebook page. He offered to recuse himself from votes, but other members said that wasn’t necessary.

Some states have tried to take emotion out of the equation by creating uniform zoning ordinances — or at least creating a statewide appeals board. Maine tried to do that when it debated a landmark housing bill in 2021, but the final legislation was watered down to preserve home rule.

Despite the group’s repeated efforts to organize residents against housing developments in Saco, most members, including Browne, Hill and Klak, insist they’re not against all development — just the developments proposed for this land.

But they bristle at being labeled NIMBYs.

“I think that calling people names, any name, is a very easy way to quickly dismiss their concerns, even if they are legitimate,” Hill said. “It’s really easy in today’s political climate to get people to immediately make a decision one way or another and not have to dive into issues like traffic, or affordability or environmentalism.”

Several people who have been involved in Saco government who spoke under condition of anonymity said they believed that the aggressiveness of the opposition to recent development projects, including Lincoln Village, has made the city less attractive to developers and discouraged residents from running for office or applying for the planning board.

“While other towns in Maine are facing similar pushback to development proposals from outspoken resident groups, Saco’s version is the most crystal clear example of civic engagement transcending into cultural gatekeeping that will actually hurt the vibrancy and strength of a community in the long term,” said one former official, who did not want to be identified for fear it could harm their business.

Meanwhile, the housing crisis has worsened since Graiver first stepped before the Saco planning board in late 2022. Inventory remains low, which has pushed prices to historic levels.

He still has another appeal pending before the Maine Supreme Judicial Court. He’s also thought about filing a federal lawsuit, but he’s not sure if he has the stomach for more time and money on this fight.

“The fact that this got rejected was a really, really big — it sucked for me — but it was a much bigger loss for the city of Saco,” he said.

Members of Save Saco Neighborhoods don’t see it that way. To them, the project’s defeat is the result of a groundswell of residents voicing real concerns and bucking the interests of developers.

Though their push to save Saco neighborhoods has largely cooled off, the group’s organizers are still busy. In fact, they have heard from people in other communities where similar housing projects are slated for development.

Said Inga Browne: “There are other projects coming through the pipeline where people are reaching out to us and asking, ‘Hey, what do we do?’”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Join the Conversation

We believe it’s important to offer commenting on certain stories as a benefit to our readers. At its best, our comments sections can be a productive platform for readers to engage with our journalism, offer thoughts on coverage and issues, and drive conversation in a respectful, solutions-based way. It’s a form of open discourse that can be useful to our community, public officials, journalists and others. Read more...

We do not enable comments on everything — exceptions include most crime stories, and coverage involving personal tragedy or sensitive issues that invite personal attacks instead of thoughtful discussion.

For those stories that we do enable discussion, our system may hold up comments pending the approval of a moderator for several reasons, including possible violation of our guidelines. As the Maine Trust’s digital team reviews these comments, we ask for patience.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday and limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs.

You can modify your screen name here.

Show less

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.